Download PDF: Greenstein, A Story of Love and Shame and Love

Abstract

The search for love can be a constructive hermeneutic force in reading sacred texts. The Zohar, the central text of the Jewish mystical tradition, applies such an approach to a Biblical text—the story of the burial of the Matriarch Sarah by her husband, Abraham—a text which seems to avoid the emotional issues of that scene while concentrating on its transactional business. By, in turn, applying a hermeneutics of love to the Zohar’s own expansion of the Biblical story, we are able to reveal layers of meaning otherwise buried beneath the surface.

Searching for Love

Where is love? Inside us? Between us? All around us? Or not? Do we feel love as something fierce and personal or, perhaps, as something intangible and afloat? Even when we may feel love within ourselves, we also seek it out. We search for love. Because love comes and goes. We seek it in our intimate relationships with parents and children and family members and close friends and with romantic partners. And they come and go, as well. We may seek love everywhere and we may find it everywhere, or, at least somewhere. The lover in the Song of Songs runs through the streets seeking her love, suffering abuse and beatings for her seeking.[1] Or we may fail to find love. Then our beating hearts shrink out of our unmet need for love and it is never assured who will be strong enough to keep looking for it.

Students of sacred scripture may search for love in the texts that they love. Jewish tradition affirms through our daily prayers that our Torah is the expression of an eternal and abounding Divine love. But beyond that grand and abstract truth, and beyond any explicit Biblical mentions of love itself, lovers of the Torah also seek out love’s tonality, or the telltale evidence—the smudged fingerprints and footprints—that love has left behind in the stories and even in the laws of the Torah. How has Divine love found a home in the individual human heart, in love for others, in shaping and enriching lives and in overcoming the failings, pains and sorrows of life? We daily thank God for granting us, from out of God’s radiant Face, ahavat hesed—the love of love, the desire to detect and identify the great love that we yearn for.[2]

This search for love can be a constructive hermeneutic force in our reading of sacred texts, both legal and narrative.[3] That is, the conviction that love resides in the text, even when unmentioned, even when seemingly absent or denied, can lead us to stubbornly seek out the presence of love in the text and expand our apprehension of that text, that law or that story, in ways that can make us stretch and grow, or at least become open to deep complexities and perplexities. As an example, we may cite the famous phenomenon of the variation in the Name of God as found in the Hebrew Bible. It has given solid grounds to readers to separate strands of texts from each other. If the text calls God “YHVH” and not Elohim, or the opposite, this is a signal that the text derives from a source that knows not the other Name. Traditional Rabbinic teaching, invested as it was in reading the entire Hebrew Bible as one coherent message, adopted a different approach. It divided the usage of these Names in terms of Divine attributes. Elohim refers to God in the mode of rigorous judgment. YHVH, a name that can be clearly associated with Being itself, was pushed into another connotation. It referred to God in the mode of love.[4] Thus the sages posited that love was to be found in countless places in the text if we just knew how to spell it correctly. Moreover, the dissonance between such a meaning and the patent use of that Name in places that do not speak of a loving God produced a struggle to stretch our perceptions in order to find love even in stories and laws that do not at all suit our comfortable notions of love. I believe that such struggles can lead to worthwhile, if discomfiting truths.

In addition, the conviction that love is to be found even in uncomfortable texts, if one seeks it out with persistence and faith, can sometimes open them up to new readings that are not hurtful or, at least, are uncomfortable in a different way. Thus, I have attempted, elsewhere, to show how this might work when reading some particularly challenging legal verses in the Torah.[5]

In this essay I would like to explore a Biblical narrative through the lens of seeking out love. The story is about the burial of Sarah, the first Matriarch, by her husband, Abraham, the first Patriarch. The short narrative, in the twenty-third chapter of Genesis is elaborated upon by the Zohar, the greatest work of Jewish mystical tradition, produced at the end of the thirteenth century in Spain.[6] The approach of the Zohar, which inherited a rich tradition of Jewish Biblical expansion (midrash), moves that tradition forward with surprising twists and turns. Behind much of the Zohar’s imaginings is its apprehension of Abraham as more than just a righteous person. For the Zohar, Abraham is the human instantiation of God’s Love.[7] Its task, then, was to understand how Abraham, as Love, would bring the love of his life to rest. In the Zohar’s retelling the practical and the spiritual embrace.

The Business of Love

Abraham was 75 years old and Sarah was 65 years old when they embarked on their rocky road together, heeding God’s call to leave behind everything and everyone they loved, in order to become a blessing to the world (Gen. 12).

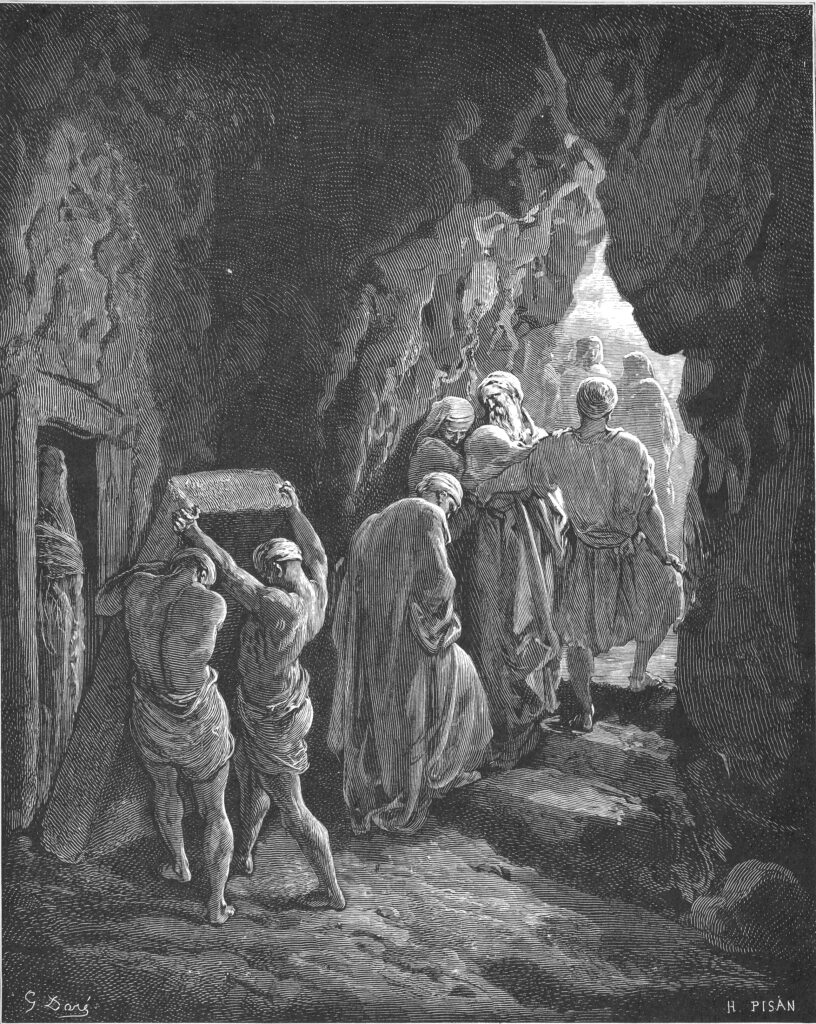

Some 62 years later their journey together ended with Sarah’s death (Gen. 23). Abraham came to Sarah’s place in Hebron to eulogize her and to bewail her. But he also had to deal with the practical matter of her burial. He negotiates with the local authorities to acquire a certain cave for this purpose, the Cave of Makhpelah (Cave of Doubling). There he buries his wife and partner. The emotional experience of Abraham’s mourning is conveyed in a few words (vv. 2-3). Abraham “came to cry,” but did he actually weep? The text is silent. Abraham’s eulogy is not recorded. But the business negotiation required in order to get possession of the burial plot consumes 16 verses, the bulk of the chapter. Where is love to be found in this text?

Some readers may find the very question inappropriate. But, if we are like the lover running in the streets of Solomon’s Song, we are not deterred. The Zohar, the central text of Jewish mystical tradition, teaches that Rahamana liba ba`ei—the (Divine) Lover seeks—or demands—or needs—the heart.[8] And so the Zohar seeks to imagine what must have been going on in Abraham’s heart, not so much when he wailed and spoke his eulogy, as when he negotiated for the purpose of acquiring his burial plot. If there is so much more recorded about that action, then the field is wide open for finding love there. And if there is love hiding in the words of a simple business negotiation, then whose love is it? And for what or for whom? And if love is hiding in those words, can we discern how love’s hiding affects those words? Or, perhaps might we discern how the words’ misdirections serve to hide the love within them?

Abraham first approached the Hittites with a general plea to grant him a permanent burial plot so that he could bury his deceased. (Gen. 23:4) Only after the locals agree that he can have any gravesite he wishes, does he get specific and ask for the Cave of Makhpelah. (v. 9) So the Zohar wonders what Abraham really desired. How did he decide to ask for the Cave of Makhpelah? And, if that is what he wanted, why didn’t he say so at the very beginning?

The Zohar’s answer is that Abraham indeed knew about this special cave for some time and desired it because of the surprising discovery he made there:

Rabbi Yehudah said, ‘Abraham knew of a unique mark in that cave, and his heart and desire were set on it. For, way before, he had entered there and had seen that Adam and Eve were buried there. And how did he know that it was they? Because he saw his [Adam’s] visage and an opening to the Garden of Eden opened for him there. And Adam’s visage was set by it. […] He saw a light in the cave and one candle burning. Then Abraham desired that his dwelling be in that place and his heart and desire were always in/for the cave.’[9]

Abraham’s heart is filled with continuous desire to be settled in that cave. Like a lover, he can think of nothing else.

The Zohar has piled upon Abraham’s heart layer after layer of emotional turmoil. Deep feelings about his personal past and his personal end—the end of his joined life with Sarah and his certain death, as well—are mixed with his passion to bind his destiny with his forebears. He thought not of his own parents and family. He had abandoned his birthplace, land and father’s house (Gen. 12:1) long ago in order to embark on a journey of discovery on behalf of God. But there were ancestors who meant everything to him, though he had never met them. When he and Sarah decided to leave together they undertook to create a new beginning, to be a new Adam and Eve. Now he had discovered that the chain of tradition from Adam and Eve to Sarah and him could be galvanized through this cave. Finally he could bring Sarah to rest next to the First Couple, Adam and Eve, at the gate to the Garden of Eden. And he knew that he would follow her there.

How had Abraham discovered the secret treasure hidden in the cave?

R. Eleazar said: ‘When Abraham entered the cave, how did he come to enter it? It was because he had run after a calf, as it is written, “And Abraham ran to the cattle,” etc. (Gen. 18:7) And that calf ran away to that cave and he went after it and saw what he saw.

This explanation presents Abraham’s discovery as the result of a coincidence of his own righteous hospitable efforts—he wishes to provide a meal for his (angelic) guests—with what seems to be pure happenstance. The wayward calf draws him to an unforeseen destination. In seeking to gain possession of a calf, he gained possession of a secret. This episode also serves to date Abraham’s awareness of the special nature of the cave to some 38 years earlier, when the angel-guests had come to announce that Sarah would conceive a son. So Abraham had been silently nursing this desire for decades.

The Zohar immediately offers an additional (independent?) factor by which Abraham came to know about the cave:

Also, [it was] because he would pray every single day and he would go out to that field that gave off supernal fragrances. And he saw a light coming out of that cave and he prayed there. And it is there that the Holy Blessed One spoke with him. That is why he wanted it,[10] for his desire was always for that place.[11]

In this scenario the discovery is due entirely to Abraham’s spiritual practice. And his discovery stems from a fragrance and a light that emanated from the cave, outside, into the surrounding field. Indeed, the field, itself, sends forth its own spiritual aroma, signaling the Divine Presence. There Abraham had been praying for years.[12]

“And it was there that the Holy Blessed One spoke with him.” Does this refer to the promise of Isaac’s birth? Or does it mean to say that it was in this cave that Abraham argued with God in order to save the sinners of Sodom and Gomorrah as he “remained standing before the Eternal”? (Gen. 18:22) This cave is the meeting ground for Abraham’s generous quality of hospitality, his desperate yearning for a son, and his stalwart demand for loving justice, even from God.

For both R. Yehudah and R. Eleazar, Abraham had been drawn to the cave for quite some time and had wished to possess it. Yet Abraham delayed. “And should you say, ‘If so, why did he not ask for it until now? It was so that they would not pay attention to it. [He delayed] since he did not really need it. Now that he needed it, he said, “This is the time to ask for it!”[13]

Abraham was caught between his yearning for this place and his fear that, should his yearning become known, the Hittites would decide to explore it themselves and refuse to relinquish it. Moreover, when Abraham discovered Adam and Eve in the cave he also came to understand that, by this time, no one else knew any longer that the First Couple was buried there. This was a discovery that the local population had failed to preserve the memory of these ancestors. How could that have happened? Abraham could not trust that the Hittites would honor this sacred burial ground, for they had inherited a tradition of disregard for it. “I am a stranger resident among you,” (Gen. 23:4) he says to them – words of humility, but also of mistrust.

This was a fear that Abraham knew well. He had tried to keep his love for Sarah, as his wife, a secret from Egyptian and Philistine neighbors, for fear that they would abduct her and kill him. But, in those instances, he was not able to devise a strategy that could protect both of them. He failed to protect Sarah although he seemingly succeeded in protecting himself.[14] So this cave was also a possible repository for his feelings of guilt and shame toward his wife. He had been willing to relinquish possession of Sarah if it would save his life, but the fulfillment of God’s covenant demanded that they not be separated. So, miraculously, through no effort by Abraham, Sarah had been restored to him again and again.

What of the cave? It was up to Abraham this time. Abraham had to live for years with a love that kept him hoping to someday gain it for himself. And, in order to keep it from desecration until that moment might come, he had to keep it secret. Now, with Sarah’s death, the need to acquire the cave for a final resting place could no longer be put off. It was only by the loss of his love in human form—Sarah—that he could now try to gain possession of his love in the form of a field and cave. But he needed to take possession of the cave without revealing the secret. He could admit that he needed a burial place for his wife, but he could not admit the deeper significance of that specific spot. So he once more uses Sarah in order to gain something else. Thankfully, this time it would be for the benefit of them both.

For the Zohar this is why Abraham had to be so careful. He starts off his inquiries in a casual and general way and then he proceeds with the negotiations. But these standard words of bargaining hid within them deep eddies of emotion, memory and hope, just as the cave hid Adam and Eve and the opening to the Garden.

Uncovering Shame

For generations the cave hid the First Couple and the entrance to the Garden. Even its owner at the time of the story, Efron, “saw nothing [there] but darkness, and therefore he sold it.”[15] The cave was precious only if one loved it. That is why Abraham could make an offer and Efron would accept it. For, otherwise, “If a person would offer all his household wealth for love, they would completely scorn him.”[16]

Abraham enters the cave and meets Adam smiling at him. Adam explains: “The Holy Blessed One hid me here. And from then until now I was hidden away as in limbo – until you arrived in the world. Now, from here on in, my existence and that of the whole world is because of you.”[17]

Our perspective has been abruptly shaken by this new development. We have followed Abraham’s story, from his viewpoint, learning of his love and hope and persistence. He has sought for so long to gain a last resting place next to the First Couple and next to the opening to the Garden of Eden and he has finally succeeded. But now we learn that he is not the only one who has been consumed with anticipation. And he is not the only one who has lacked a final resting place. We learn that Eve and Adam have been waiting all this time to see whether someone would seek to pick up from where they left off, to pick up the pieces that they dropped. We learn that Abraham’s need to be with Adam and Eve is nothing compared to their need for his devotion, a devotion that has redeemed them from their endless years of insecurity. Because Abraham never lost his love for his spiritual parents’ long past, they are now vouchsafed a spiritual future. With Abraham’s burial of Sarah, Adam and Eve will be securely buried at last.

This new turn in the story has surprised us but also pleased us. It is satisfying to come to this place of rest, achieved through mutual concern. But just as we are ready to embrace this sense of an ending, Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai, the master teacher of the Zohar, again surprises us by re-opening our story with an unsettling continuation:

Said Rabbi Shimon, “At the moment when Abraham entered the cave and brought Sarah there, Adam and Eve arose and did not agree to be buried there. They said, ‘How ashamed we have been in that world before the Blessed Holy One because of the sin we brought about. Now more shame will be added for us in the face of your good works.’”[18]

What we had hoped would be a loving resolution, long sought after, produces its own new problem. The faithful righteousness of Abraham and Sarah puts the First Couple to shame! How did Abraham’s righteous fidelity turn from being redemptive to being shaming? Some readers have understood the problem to be Abraham’s unblemished life as compared to the tragic sin committed by Adam and Eve. But that potentially damning comparison was obvious before, when Adam hailed Abraham as his hero and savior. We must conclude that something else, some new element, is the matter.

That “something else” is the ushering in of Sarah into the cave. Adam’s conversation with Abraham, thanking him for his saving righteousness, for rescuing Adam from an unresolved fate, took place between the two men, without reference to their spouses. But now Abraham has brought Sarah into the cave to bury her. This belatedly loving act, fraught with memories of tensions and recriminations, an act meant to redeem Abraham from any past thoughtlessness, if not faithlessness, to Sarah, is, for Eve and Adam, too much of a good thing. To them this goodness has become a taunt, a shaming accusation, rather than a source of comfort and peace of mind. Their shame washes over them in doubled force. Abraham and Sarah have become the First Couple and Adam and Eve cannot bear to lie there next to them, a failed copy of those two.

“Abraham, My lover.”[19]

None of this was Abraham’s intention. His dream was of communion. But his very achievement of that dream poisoned it for his beloved elders. His love was too much for them to bear. Because his love shamed them in their own eyes, they now refused to enter into and share a space with him. How could he redeem his dream from ruin? How could he take away Adam’s shame?

Said Abraham, “Here – I am prepared to stand before the Holy Blessed One on your behalf, so that you shall not be ashamed before God forever!” Immediately, “And after that Abraham buried Sarah, his wife”! (Gen. 23:19). What is “and after that”? – after Abraham took this matter upon himself.[20]

But is this how shame is removed? And, if it is Abraham’s extraordinary love that shames Adam, shouldn’t Abraham’s new offer of extreme selflessness just engender even more feelings of shame in Adam’s heart? Can shame be thwarted? Does shame depend on some mechanism that can be controlled or dismantled?

Abraham undertakes to stand before God on Adam’s behalf. How will this help? Does Abraham stand before God to plead for God to erase Adam’s shame? Can God actually excise that feeling from Adam’s burdened heart?

Or does Abraham stand before God as a screen, an obstruction, preventing God from looking at Adam with that gaze that Adam dreads, exposing his puny nakedness? Perhaps Adam can thereby avoid God’s shame-inducing gaze. “You have distinguished the human being from the start, recognizing them so that they might stand before You.”[21]Adam was meant to be able to stand before the Creator, but he could not do it. So Adam then sought to hide from God’s displeasure, but unsuccessfully. Now Abraham promises to stand before God for his sake. Was Abraham the screen of atonement that Adam had needed all along? What made Abraham such an effective cover?[22]

Abraham’s love has created a tragic difficulty. Instead of granting Adam his much anticipated rest, it causes him humiliation. But Abraham senses that the only way to overcome this problem—or, at least, the only way open to him to overcome this problem—is with more love. Abraham hopes that his loving intercession before God can wash away from Adam any qualms of shame. So perhaps Abraham is not so much a cover or screen, but a lens, a speculum through which Adam can see that God’s displeasure or disappointment have been dissolved in love. Abraham is not merely Abraham, God’s lover. Abraham is also, for the Zohar, Hesed – God’s Own Loving! When Abraham stands before God it is as if God’s Love stands before any of God’s other attributes. Thus it steps forward and stands before Adam. Adam no longer needs to feel ashamed. Whatever Adam had done or caused has no effect on Abraham’s love. It is as nothing. It no longer is. And Adam’s soul is put to rest.

And the reader is prepared to rest as well, along with the ancients. But the Zohar has one more astounding move before she is ready to lay this story to rest. The Zohar does not miss a beat, and after this dramatic gesture by Abraham that allows the burial to take place, it immediately remarks:

Adam entered his place; Eve did not – until Abraham approached and brought her in to Adam, who welcomed her because of him. This is just as it says, “And after that Abraham buried Sarah, his wife.” It is not written “prepared the burial for Sarah.” Rather it says “et Sarah – [buried] along with Sarah,”[23] to include Eve. Only then did they settle in their places as appropriate.[24]

How easy it is for the reader (especially a male reader with a love of the tradition—who, until recently has been the only reader of the Zohar) to follow the Zohar’s story, raptly listening to the dialogue between Adam and Abraham, and forget that Sarah and Eve are also present! What are their feelings, their reactions, their words? The Zohar does not give either woman speech. But it does recognize that this story of love and shame cannot be concluded without bringing the two Matriarchs back into our regard.

So we are pulled up short when we are told that Eve is not simply the automatic follower of Adam. Her reaction is a complex combination of independence and surrender. On the one hand, Eve does not accede to Adam’s decision to take his proper resting place. She does not accept the assurances offered by Abraham. But this means that she also does not feel affirmed and reconciled. She feels shame that is both debilitating and empowering. She feels incapable of accepting her worthiness; she feels so strongly convinced of this that she will not obey the wishes of her husband or her rescuer.

What was the source of her powerful sense of shame? Before whom was she ashamed? Apparently, Abraham’s successful intercession with God to eliminate Adam’s feelings of shame did not address the core of Eve’s shame. It was not God’s gaze that Eve could not bear. It was Adam’s. She could not bear his look of accusation and resentment. Instead of accepting Eve’s thoughtless act of sharing as an act of love, albeit misguided, Adam blamed her for handing him the Tree’s fruit. The unsettled state of this First Couple was the fruit of a failure to reconcile, not solely with God, but with each other.

But now Abraham finds a way to overcome Eve’s shame as well. He ushers her into the cave along with Sarah (“et Sarah”). How does this change anything? Why should Eve relent now? The Zohar explains that Adam “welcomed her because of him.” The interconnecting threads of emotions run between each of these four persons and the others. The combinations are many. Perhaps Adam lets go of his anger at Eve in the face of Abraham’s overwhelming love for Sarah. Or is it Abraham’s forgiving love of Eve? Or, alternatively it is because of Sarah’s forgiving love for Abraham? For, although she is silent, her silence must be understood as assent. She agrees to have Abraham place her in this cave, where he will eventually lie next to her. This is not to be taken for granted—for just as Eve could refuse to enter this place of rest, so could Sarah have refused. Thus Sarah’s love, unremarked, is wholly necessary for this arrangement to work.

Sarah’s role is delicately, subtly acknowledged. And this allows us to read the ending in one more way. When Adam welcomes Eve, we can read this gesture without ascribing to it hierarchical authority or power. The welcome was not waiting for Adam to offer. Rather, Adam was waiting to be able to welcome Eve, unable to do so until Eve would be amenable to it. Eve’s shame was both a wound inflicted upon her and also a source of her demand for justice, if not love. If Adam would not overcome his own antagonism, Eve would not meekly accept it “lying down.” What or who could change Eve’s mind? Perhaps it was Sarah who changed Eve’s mind, for Eve was only ready to enter her place “et Sarah”—along with Sarah. When Sarah enters the cave with Eve, Sarah embraces Eve at the same time that she embraces Abraham and allows him to embrace her. Abraham has been welcomed by Sarah, and therefore Adam can welcome Eve because of him. Sarah shows Adam that he must love Eve just as she shows him that she loves Abraham and Eve. Eve’s shame dissolves in this web of love.

Practical Matters

The Torah tells a story of a burial in a way that seems to emphasize the practical aspects of the task while hardly touching on the emotional currents coursing through the story’s participants or the deep significances such practical matters may have carried for them and despite them. The Zohar, convinced as it is of the essential bond between the mundane and the transcendent, opens up this story so as to uncover the many layers of feeling buried within it.

Abraham’s discoveries are made possible by practices both consistent (constant prayer) and spontaneous (improvising a meal), and they are motivated by impulses toward practical need as well as toward spiritual communion. In all these spheres the common thread is love. Even his seemingly most prosaic act of negotiating for a piece of land can now be seen both as an expression of love and as a protection of that love. Just as the cave shelters the beloved by covering their body with earth and darkness, so does the text hide the patriarch’s love from unloving eyes. Like Abraham in the original story, the Zohar uncovers in the text (i.e. the cave) hidden elements and meanings that have been waiting for redemptive intervention by a questing lover.

For the Zohar this story teaches that what is buried and forgotten may yet be rediscovered and restored to meaning.[25] In doing so it makes possible a further expansion of our reading of its reading to unearth even more elements that lay just beneath the surface of this story. Does such an expansion take us beyond the original intentions of the Zohar’s narrators? How would those earlier storytellers feel about such an exploration? I choose to believe that they, like Adam and Eve, would—perhaps hesitantly, at first, but eventually—welcome it with shameless love. And this welcome would make space for us, like Abraham and Sarah before us, to join them in the cave, a cave that opens up only to the those who seek to enter it out of love.

Notes

* This essay grows out of a study of this text with my dedicated partners in our weekly Zohar study sessions at Congregation Shomrei Emunah in Montclair, NJ. I acknowledge them with great appreciation.

[1] See Song of Songs 5:6ff and 3:1-4.

[2] In Micah 6:8 we learn that this “loving of love” is demanded of each human being. The phrase is part of our prayer for peace, the last blessing of the central morning prayer.

[3] The Hasidic leader, Rabbi Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter of Ger (1847 – 1905), taught: “Therefore the Thirteen Attributes of Divine Mercy […] correspond to the 13 rules for interpreting the Torah. It is recorded in the books [see Zohar 3:62a] that the Thirteen Attributes of Divine Mercy are the root of the 13 hermeneutical rules of the Torah. They are all one thing.” (S’fat Emet, Ki Tissa, homily of 1896)

After writing this essay I came across Alan Jacobs’ A Theology of Reading: The Hermeneutics of Love (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2001). I am not able to fully engage with that work here. Jacobs writes from a Christian viewpoint. But I believe that my approach, besides in its being rooted in my Jewish engagement, may also differ from his in being less insistent on a confessional element as either its grounding or its goal.

[4] See Sifre D’varim 26, and see Rashi to Gen. 1:1, s.v., bara Elohim.

[5] See my essay, “Pithu Li Sha`arei Tzedeq – Open the Gates of Righteousness for Me: An Opening Toward a New Reading of the Torah in Light of the New Status of Gays and Lesbians in the Jewish Community,” The Journal of the Academy for Jewish Religion 3:1 (5767-2007), pp. 1-21. Available on the Shomrei Emunah website –

http://www.shomrei.org/media.asp?catid=16&showdetails=1

And the academia.edu website –

https://www.academia.edu/9137619/Pitchu_Li_Shaarei_Tzedeq

Another version of this essay was later published in The Sacred Encounter: Jewish Perspectives on Sexuality, ed. Rabbi Lisa J. Grushcow (Philadelphia: CCAR Press, 2014), pp. 43-56.

[6] Zohar 1:127a – 128b. I will offer my own translations unless otherwise noted. See also, for this entire text, D. Matt’s excellent translation and notes, The Zohar: Pritzker Edition, Vol. II (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2004), pp. 219-223. My translation occasionally diverges from his.

[7] See Zohar 1:96a and many other places.

[8] Zohar 3:281b (RM). The Zohar substitutes the more emotionally charged name Raḥamana—Merciful or Loving One—for God instead of the Talmud’s original formulation: Qudsha B’rikh Hu—the Holy Blessed One [needs/seeks/demands the heart]. See BTSan. 106b.

[9] Zohar 1:127a.

[10] Or – “asked for it.”

[11] Ibid., 127b.

[12] The Zohar applies to Abraham an earlier tradition that identifies Isaac as praying in fields. See Rashi on Gen. 24:63, quoting Gen. Rabbah 60:14. His devotion to his constant practice of prayer in the field leads him to his wonderful discovery of Divine Presence in that place. The sages saw Abraham as the first to pray the morning prayers. (BTBerakhot 26b) Such a retrojection adds sanctity and weight to traditional practice, of course. But it also puts additional pressure on the contemporary practitioner. For the follower of traditional practices adopts those practices precisely for their established sanctity, while the founders of such practices (Abraham, here) were first seeking after sanctity and divine connection rather than seeking refuge in a known act or place. Thus, the contemporary practitioner, in emulating the practice of the founder, is challenged to engage in a known practice while yet hoping to regain something of the original experience of experiment and discovery.

[13] Zohar, Ibid.

[14] See Gen. 10:12-20 and Ch. 20. For an instance where Sarah complains to Abraham that he is not standing up for her see Ch. 16, and for God’s support of Sarah against Abraham, see Ch. 21:9-13.

[15] Zohar 1:128a.

[16] Song 8:7.

[17] Zohar, ibid.

[18] Ibid. The second person “your,” in “Your good works,” is in the plural, referring to both Abraham and Sarah.

[19] Isa. 41:8

[20] Zohar 1:128a-b.

[21] From the concluding prayers of the Day of Atonement.

[22] In Biblical Hebrew the word for atonement – kaparah – also means “covering over.”

[23] The seemingly superfluous indicative particle “et” is often read in rabbinic literature as a signifier that, along with the object explicitly mentioned in the Biblical text, something unwritten is additionally included. See Matt’s note 151, p. 223.

[24] Zohar 1:128b.

[25] A Postscript: This essay was written before the coronavirus pandemic overran our world. Since then I—and others—have had to bring loved ones to burial under severe constraints that precluded the physical presence of family and friends and that curtailed the expressions of love and sorrow that have always accompanied these rituals. Each burial under these circumstances is a burial that awaits its loving redemption at some time in an unforeseeable but hoped-for better future.