[S]ince war begins in the minds of men [humans], it is in the minds of men [humans] that defenses of peace must be constructed.

This quote prominently embedded in the UNESCO Constitution is certainly not an original thought. It is the based upon the ancient Vedic aphorism: “War begins in the minds of men.”1 However, as we see, the UNESCO statement suggests a pragmatic recommendation, and not just a static description of the origins of war. It is both aspects of this statement that capture the themes of this essay: the internal processes of the mind and spirit, how we view “the other,” and its relation to violence, war, and peace. I offer this discussion to those of us who exist in a highly pluralistic global context, who often wrestle with “difference,” and yet consider ourselves committed to spirituality, peace, justice, nonviolence, and tolerance. More pointedly, I direct it toward those who like me, despite our best intentions, are often unaware of the many ways in which we devalue and dehumanize others in our thoughts and attitudes, or the potential consequences of such thinking (i.e., how do we construct those defenses of peace?). As we shall see, how we view the “other” is the critical component to either peaceful or destructive relations with others. The direction we assume hinges upon our views of the other. For those of us concerned with putting spiritual resources into practice to promote peace, connection, and justice in the world, we must work to make our thoughts, words, and deeds consistent with these goals. For educators, we must be open to both appropriating and communicating new practices to help advance peace and justice.

In what follows, I present a useful conceptual tool for understanding the insidious process of what I call “othering.” I then present a contemplative tool for assisting us in combating this tendency and, in fact, reversing its direction. I do so using social science concepts in conjunction with contemplative principles and practices. Like many seeking new ways to understand and address proverbial problems, I attempt to draw a unique connection. Thus I present psychologist Ervin Staub’s “continuum” model of destructive and benevolent relations, and expand its original application to enable it to function as a useful contemplative discipline for internal inventory and mental monitoring. Using this tool can affect our attitudes as well as our actions.

Virtually every religious, philosophical, and humanistic tradition deals with the phenomenon of human disconnection from, disregard for, and dehumanization of others. While it is impossible to address the devaluation tendency from every perspective, for our purposes psychology and psychobiology offer a relevant contribution. Psychobiologists talk about the evolutionary function of human disconnection and even dehumanization as a matter of survival. In essence, the theory posits that quickly classifying people into subgroups such as “good” and bad,” “us” and “them,” or “friends” and “enemies” was a necessary survival mechanism rooted in human evolutionary physiology. This classifying function once served the emerging species well in protecting and preserving humans from physical threats or harm; at times it still does.

These same evolutionary processes were the precursors to the stereotyping, homogenizing, and devaluing that we practice today and form the foundation of what I call “othering.” Othering refers to the targeting of those outside of our internal sphere in ways that dehumanize and degrade them or violate their dignity. It denotes a destructive process by which humans disconnect emotionally, physically, and socially from other people for real or perceived reasons.

Whether one accepts the presence of these psychobiological “imprints” or not, the fact remains that it is to a certain extent “natural” to classify others as threats to our survival or well-being. It is ingrained within us to evaluate, judge, and classify the “other.” “Modern” humanity, however, engages in this practice for social as well as physical reasons. Thus as individuals and collectives, we over-classify in relation to how the “other” impacts our status, honor, prestige, position, or identity. Thus, othering takes natural human tendencies, whether primordial or evolved, and distorts their original intention (i.e. survival), thereby creating new and destructive categories and applications, and contributes to the overall dehumanization of all involved.–when, for example, we “protect” ourselves by “justified” retaliation against or even elimination of the other. Pyschobiologists ascribe this locked-in tendency to the “primitive brain” that we all posses.

Two important points follow once we recognize the psychobiological basis of this tension between self and others. First, that we as “modern” humanity engage in this sort of “justified” retaliation more than we realize. In fact, we are often unaware of the “othering” tendencies that fuel our hostile actions. Negative messages about others are fed to us by family, peers, media, religions, mentors, culture, or any number of other vehicles. We hear, adopt, and appropriate them as our own. Like seeds that are (im)planted, our negative attitudes can be “watered” to grow into hostility and violence toward the other. The humanity of the other can become overshadowed by our perception of him or her solely as an irritant, threat, enemy, or pollutant that must be dealt with or eliminated altogether. The second point is related to the first: this development often takes place in an incremental,progressive fashion. We express our negative perception of the other in ways that run the spectrum from distancing to devaluing, marginalization, oppression, hostility, violence, and even murder and genocide.

These two points form the critical basis from which to move forward. The seemingly unconscious, incremental, yet progressive development of attitudes and behaviors cannot be underestimated in understanding the nature of violence and peace. From here we understand that violent actions do not just appear out of nowhere. They emerge when certain trajectories and patterns are set in motion.

Therefore, there is great benefit to having a theoretical tool to help us understand the patterns, trajectories, and significance of movement along a spectrum of human relations—and to be able to recognize our movement or location at any given point along that continuum. Psychologist Ervin Staub presents us with both a conceptual and practical tool for understanding these principles based upon empirical research. However, as we shall see, these very same concepts pertain not only to the practice of destruction and violence, but also to benevolence and peace. When coupled with contemplative principles, we discover that empirical social science findings can be appropriated as a form of spiritual practice and discipline.

The Continuum

The idea of a continuum exists in many areas of knowledge and study. It can be found in the physical sciences, human relations, or any other area in which degrees of intensity, escalation, or de-escalation are measured. In monitoring human relations, continua are useful because they allow us to gauge closeness or distance, harmony or destructiveness. We can draw the following general categories that concern violence and peace within human relations from a variety of social science disciplines: 1) separation, 2) stereotyping, 3) superiority, 4) dehumanizing 5) scapegoating 6) demonization. A visual representation of this continuum might look like:

Separation -> stereotyping -> superiority -> dehumanization -> scapegoating -> demonization

If we add undesirable “religious” elements, such as destructive mythologizing or concepts deriving from a sense of chosenness or superiority, for example, these translate into different types of atrocious actions along the continuum. We can even add a new category: Satanization.2

These continua certainly represent distinct progressions toward destructive relations; however, they share a common starting point involving “separation” and “stereotyping.” Ervin Staub’s continuum is useful because it emphasizes the significance of these starting points and has a direct empirical basis in a real human process.

Staub’s Continuum of Destruction

Ervin Staub, a psychologist who writes extensively on the psychodynamics of violence, particularly the origins of genocide and mass killings, presents us with an instructive and useful model that includes both a continuum of destruction and a continuum of benevolence. The continuum concept is a major anchor of his overall theory of psychological impulses toward violence. He identifies the beginning stages of incremental movement along the continuum of destruction as “the roots of evil.”3 Our purpose here is not to go into the deeper nuances of Staub’s model, but rather to understand it as representative of a recognizable human phenomenon.

With his continuum model, Staub highlights a recognizable and predictable pattern that has led to atrocious acts of violence, mass killing, and genocide. The foci of his analyses are the catastrophic displays of inhumanity that occurred in Nazi Germany, Cambodia, Argentina, and Turkey. His analysis takes place primarily at the level of group dynamics, but applies to individuals as well.4 What his studies reveal is that these horrific instances of violence all began with the devaluation of certain groups, proceeded to marginalization of those same groups (i.e., to covert discrimination and denial of civil, social, or political rights, etc.), moved on to overt discrimination, and culminated in open resentment and aggression toward groups identified as suitable targets of hostility and violence. In the end, these groups were labeled as “enemies” and identified as causes of prolonged difficulty that consequently had to be eliminated (or exterminated). We can visually represent this progression as follows:

Devaluation -> marginalization -> discrimination -> resentment and aggression -> hostility -> dehumanization -> elimination (extermination)

In this sequence, Staub identifies one crucial element that had a precipitating effect. When groups or nations experienced what he calls, “prolonged difficulty”—whether political upheaval; economic distress; varying degrees of social anarchy; or ongoing perceived threats to a group’s identity, sense of autonomy, or rights—those conditions intensified to a tipping point that set the downward spiral in motion. His theory is complex, as it also accounts for a society’s attempt to fulfill powerful needs that arise during prolonged periods of difficulty and that become fulfilled in destructive ways. The guarantee of destruction occurs when the society devalues, marginalizes, and oppresses certain groups, places cultural premiums on obedience to authority, and begins aggressive measures to “root out” the problem.

Staub’s great contribution for our purposes is the following observation: although the violence and barbarity reached atrocious levels in the cases that he analyzed, the “roots of the evil” originated in the early stages. As time went on, attitude and action reinforced one another and precipitated lower and lower depths of depravity, often perpetrated by those who would have never imagined themselves capable of such actions.5

In essence, perpetrators make choices by giving themselves permission to take certain violent actions corresponding to the attitudes, stereotypes, or ideologies they have adopted. They especially tend to do so when they see others engaging in those actions. Having committed one seemingly less harmful act, their own moral reservation is weakened and they now see themselves as someone who is capable of perpetrating similar, more harmful acts. This “changing self concept” as Staub calls it, opens the door to a cycle of “learning by doing.” In other words, when perpetrators observe themselves or others engaged in violent, dehumanizing, or murderous behaviors, they reassess how they viewed their own abilities to inflict harm or to passively stand by when watching others in pain. As they consider themselves more and more as people who can act in certain ways, it becomes more likely that they will continue the behavior.

In analyzing how these processes take place, Staub highlights the following concepts: 1) All instances that ended with extreme violence began with devaluation and marginalization, and progressed downward; 2) there are trajectories that are almost completely predictable; 3) trajectories set in motion gain momentum with less severe attitudes and behaviors giving way to more severe attitudes and behaviors; 4) people learn by seeing and doing; and 5) seeing and doing changes the way people view themselves and that of which they are capable. People are largely unaware of all five concepts, especially because the processes that they involve may feel “natural.” The key question then becomes how to interrupt those processes. Ironically, the answer is contained within the processes themselves, if we reverse their direction.

The Continuum of Benevolence

Staub’s continuum of benevolence follows directly from his continuum of destruction. In essence, Staub posits that the same processes of sequential, mutually reinforcing attitudes and behaviors apply to a continuum of benevolence, but this time the process moves in the opposite direction. He focuses on people’s motivations for practices of prosocial behavior and benevolence, which are connected with “core shifts” in what people value as essential to their sense of life satisfaction (i.e., caring, connection, community, peace, etc.).6 These core shifts come as a result of participating in acts of benevolence. For, “as we come to value more highly the people we help and experience satisfaction inherent in helping, we come to see ourselves as more caring and helpful.”7 Individuals thereby come to see themselves as more capable of such acts, and they gain greater and greater life satisfaction and meaning from them. This process changes one’s attitude about oneself and the other as well. In essence, small acts of kindness and caring lead to bigger and more significant acts of kindness and caring, along with an increased commitment to helping others in need. In this way, people begin to build connections to a community of people who support one another’s steps along the continuum of benevolence.8

Staub’s research also demonstrates that, just as with the continuum of destruction, people, especially children, learn benevolence by doing and watching others do. In practice, he therefore prescribes creating societal opportunities for giving and service, especially for children. He refers to extensive studies that have shown the positive effects on school-aged children in both observing and participating in acts of giving, service, and caring. Their observation and participation affects their sense of self-esteem, positive self-perception, competence, potency, empathetic and role-taking capacities, preoccupation with self and self-concerns, responsibility, and benevolence to self and others. This self-concept/action cycle becomes self-reinforcing and gradually increases an individual’s capacity to extend this benevolent behavior outward.9 The continuum of benevolence can consequently be represented as follows:

Indifference -> opening up -> acceptance, (respect, dignity,) -> empathy -> caring (service) -> connection -> community -> love (increasingly outward) -> peace10

For Staub, society’s task is to create maximum opportunities for caring and connection. Doing so can help to create peaceful communities and schools for children and society in general. In fact, there are already literally tens of thousands of non-profit, church, and volunteer organizations dedicated to providing exactly the kinds of opportunities that Ervin Staub and others who study altruism and empathy advocate. People are learning by doing.

This essay, however, is directed toward those of us who are seeking new tools to both appropriate and teach in the intersection of religion, violence, peace, and religious practices. Engaging in benevolent acts with others across real and perceived difference is worthwhile, but often difficult. There are many layers of resistance, whether these come from negative messages and stereotypes, for example, or from limited prior experiences. In other words, although opportunities for connection might be abundant, our distorted perception of others might prevent us from such engagement. Thus the “natural” tendency to classify and create subgroups in the name of self-protection presents real barriers.

We can find certain resources to overcome these barriers in the forms of contemplative practice that religious and non-religious (ethical, moral, and “spiritual”) people engage in every day. In the next section, I offer a contemplative tool for taking the elements of the continuum of destruction and applying them to a continuum of benevolence. In other words, I take the components of theproblem and turn them toward the solution. To my knowledge, this direct connection has not been made in this way. We can do so by taking straightforward reflective questions and exercises directly from the categories of the two continua. Such a reflective process uses focused questions to help us to identify our own “ignorant” and unconscious destructive forms of othering.

A Contemplative Approach

A “contemplative” approach to anything is difficult to define, as the term “contemplation” encompasses a broad range of meanings. In addition, contemplation can be construed (and practiced) much differently according to various religious, philosophical, and ethical traditions. My own perspective on contemplation is Christian. However, other traditions offer similar contemplative tools that can help to combat our impulses toward othering. In general, contemplation can be said to revolve more around an attitude, outlook, or approach, than a “method” or “system.”11 In practice, contemplative methods could include spoken or mental prayer, meditation, silence, solitude, sacraments, practicing the presence of God, finding one’s “Center” or “Core Reality”, and many other practices.12

Taken together, contemplative methods constitute an approach toward the Divine, the spiritual, or the transcendent that yield new ways of “seeing” and “being.” Thomas Merton has described contemplation as deep listening and an “attitude” or “outlook” consisting of faith, openness, attention, reverence, expectation, supplication, trust, and joy. Franciscan Father and author Richard Rohr gives us a more nuanced conception, and I think a more applicable understanding of these principles in relation to our concerns about othering, violence, and internalizing destructive cultural messages. Rohr says that contemplation, in relation to what he calls “true seeing,” enables us to see through cultural hypnoses, through self-serving “truth” and cultural lies. Contemplation thus helps us to see what is always at the foundation, which is goodness and love; to see God in all things and to recognize “group think” as distinct from “God think.” Contemplation is a way of “cleaning the lens”—of gaining the ability to stand back from ourselves in order to question and reflect upon anger, predispositions, and prejudices. For Rohr, this “seeing” helps us see not only for ourselves, but also what we do to other people, especially the pain and suffering that we cause them.13

Contemplative principles are also concerned with cultivating detachment from ego, from an unhealthy “I” fixation, and from “false selves” that project blame and evil outwards. Contemplatives such as Fr. Thomas Merton and Fr. Thomas Keating have written extensively on how centering prayer can serve as a vehicle to illuminate ego fixation and personality fractures in relation to “true” and “false selves.” Merton, Keating, Rohr, and Henri Nouwen have written about the need for contemplative self-questioning and reflection in uncovering inner violence and our tendencies to project this outward.14 This process also helps in discerning destructive or violent cultural messages that resonate with our own tendencies.

We can find similar practices and ways of “seeing” and “knowing” in virtually every major world religion with any sort of contemplative strain—especially in those that emphasize the ontological interconnection of all life. Mahatma Gandhi developed an approach to peace and nonviolence, for example, that utilizes powerful Hindu contemplative principles and resources. Such resources, such as Ahimsa and Satyagraha,15 are expressed during stages of meditation (synonymous with our conception of “contemplation”) that take one from awareness of the external, to systematic control of the activity within the mind, and finally to a more expansive, unified way of seeing and knowing. For Gandhi, and others who engage in the spiritual practice of nonviolence, the nonviolent struggle begins with mastering one’s own emotions and thoughts. Waiting until the moment of conflict to learn nonviolence is too late.

There are many Buddhist teachings, from a variety of sects and lineages, that incorporate meditative and mind training practices and that go back hundreds or thousands of years. These teachings include specific contemplative or “mindfulness” disciplines that cultivate compassion, openness, true “seeing,” awakening, ego awareness and detachment, inter-connective awareness, and other reflective tools for cultivating connection, compassion, empathy, and understanding of our own inner tendencies toward cultural deception and violence. The Dalai Lama calls such practices “internal disarmament”—that is, intervening right where violence starts, “at the root of hostile thoughts.”16

It is also entirely possible for non-religious persons to engage in the types of awareness that we have described simply by virtue of a conscious commitment to living out prosocial or benevolent ethical values and principles. Even without making use of overtly religious practices, people can still undertake “spiritual” practices by, for example, adopting principles that enhance the “human spirit.”17 It is practicing with conscious intentionality that matters.

Therefore the following reflection questions can represent contemplation, meditation, internal disarmament, or whatever label one finds useful. One term that I happen to find useful comes from Alcoholics Anonymous: during the recovery process from addiction—and it’s not a stretch to think of ourselves as “addicted” to separating, devaluing, self-justification, blame, and hostility—the program promotes the daily practice of a personal inventory or “spot check inventory” to assess one’s frame of mind in relation to sobriety or “triggers” toward negative emotions or relapse (part of Step 10). One then immediately communicates these thoughts, feelings, and frames to a “Higher Power,” sponsor, or another person, thus inviting instant connection with others and a corresponding sense of accountability for destructive thinking, feeling, or behavior patterns.18 “This connection to god and understanding my destructive behaviors, when done at a drug rehab center near me with a trained doctor, was an experience from which I was able to take away a lot more than when I tried the 12 steps at home”, reports one patient. We may refer to the practice of leading oneself through the following sets of questions as a form of prayer, meditation, contemplation, or “spot check inventory.”

Contemplative Action Questions

When we find ourselves entertaining negative frames of the other, we can employ these three sets of questions that revolve around three major “moments” or actions:

1) Recognize, 2) Reflect, and 3) Reverse, which correspond in turn to three further actions: 1)Awareness, 2) Arrest, and 3) Altruize.19 This three-step process, or spot check inventory, facilitates 1) Recognition (awareness and acknowledgement of feeling, attitude, perception, 2) Reflection (arresting the trajectory through a recognition of the importance of this awareness, probing a “truthful” response to feeling, attitude, and perception) and, 3) Reversal (contemplative action as willingness to act on this response to change directions—to altruize ourselves and re-humanize the other).

- Recognize (Awareness):

From a general standpoint, we may ask ourselves:

- Do I see myself as completely separate from this person?

- Do I feel superior to him or her? If so, how, and why?

- Do I see him or her as fundamentally different from me? If so, in what way?

- Does what I’m feeling or observing contain elements of devaluation? In what ways am I devaluing this person?

- Is my attitude stronger and more like marginalization?

- Is it even stronger and more like dehumanization?

- Has it gone so far as demonization? Have I identified this person or group as the sole cause of my (our) suffering, discomfort, and pain, and am I feeling or thinking that they should be punished, harmed, or eliminated at any cost?

These are the “red flag” questions that serve as a warning that something is wrong inside of us. Notice the range of scrutiny that ranges between what we might consider a mild and extreme spectrum of probing. Such questions form part of a spiritual discipline because they remind us that separation, devaluation, marginalization, and demonization are not just attitudes we carry, but also actions that most likely get directed toward others.

- Reflect (Arrest):

This set of questions involves naming potential negative consequences if our attitudes are left unchecked.

- What am I doing to combat the separation, superiority, stereotype, devaluation, etc., that I am experiencing?

- What is the basis of my devaluing this person or group?

- Am I dehumanizing this person or group? How have I separated, devalued, or marginalized him or her with my language, labels, thoughts, and behaviors?

- What am I doing to combat these negative attitudes and framings that I have toward this person or group, and is it working?

- What will happen (to me or to this person) if I do not combat these feelings and attitudes?

We might call this process the “what’s at stake” phase. This portion is critical in leading us to acknowledge our self-justifying tendencies to rationalize or discount negative attitudes (and potentially destructive actions) toward others. It is the liminal moment of truth where we can choose to acknowledge what may be at stake for us and the other, and consciously decide to take action.

- Reverse (Altruize):

This set of questions represents movement, not away from something as in the previous questions, but toward prosocial relations, i.e. toward connection, caring, community, benevolence, empathy, tolerance, forgiveness, and love. Once a person has a specific awareness of his or her state of mind and has engaged in some reflection on the potential consequences of leaving the destructive momentum unaddressed, he or she needs to reverse the movement. These questions move one in the direction of a continuum of benevolence. Here one must call upon his or her religious, spiritual, and ethical resources with focus and intention and apply them directly to the current situation in order to actually move forward.20

- What do my religious, spiritual, and ethical resources instruct me to do with the feelings that I am harboring toward this person or group?

- What do my religious, spiritual, and ethical resources say about separation, superiority, and my interconnection to humanity?

- Which resources can I draw upon right now to ascribe value, dignity, and humanity to this person or group?

- Which resources can I draw upon right now to reach across faith, ethnic, class, sexual orientation, and gender lines to practice respect, friendship, humility, and the ascription of dignity and sacred transcendence to all persons as an expression of the Divine?

- Can I call upon these resources right now to go beyond tolerance and practice love in this situation?

There are two critical points to convey vis-à-vis the third set of questions. First, they of course do not exhaust the menu of reflective possibilities available in moving toward a greater sense of connection toward one’s fellow human beings. The options are virtually limitless. Second, and most importantly, although initiated intellectually, the reflective process cannot and should not constitute an intellectual exercise alone. Awareness and acknowledgement must lead to “contemplative action.” Once we have identified the necessity of employing our spiritual and ethical resources, we then have to employ them immediately. The reader will notice that the questions repeatedly contain the phrase, “right now.” As stated earlier, one can devise other questions that reflect similar themes, as long as they move one immediately in a prosocial direction.

This same process can be practiced from within any religious, spiritual, or ethical / philosophical tradition. More importantly, within the context of our daily lives, it can be practiced in the grocery line, the post-office, the gas station, and virtually anywhere and anytime we encounter others outside of our comfort zone and begin forming negative perceptions of them.

Conclusion

Violence, aggression, and war do not just happen out of nowhere. There are always precursors and patterns in human attitudes and interaction that point in destructive and even catastrophic directions. Lest we become distracted by the overt “evil” and brutality of human behaviors in the form of mass murder and genocides, we must not overlook or underestimate the practices of devaluation and stereotyping that contribute to these types of “events.” Religious peacebuilding scholar Marc Gopin articulates this concept well when he states that it is the aggregate of daily human interactions and attitudes that truly represent “the murky space in between war and peace where people and civilizations really make the fateful decisions to humanize or dehumanize the Other, even if within our own minds.”21 Thus, in our highly pluralistic world, marked by division, hostility, difference, propaganda and war, there is much at stake. In our own country, in the midst of political, racial, cultural, and religious division, there has been and is currently very much at stake.

It has been said that the “undisciplined human mind is the ultimate doomsday weapon.”22 Thus, we must be vigilant, for we risk wielding this weapon carelessly. Yes, war does “indeed begin in the minds of men [humans],” but, ironically, the “roots of evil” are also the “roots of peace.” And we have ample resources for caring, connection, benevolence, and peace. We can direct our self-reflective efforts to mutually reinforcing ends, in which contemplation turns into action and action into contemplation, as in Thomas Merton’s image of the spring and the stream: If the waters of the spring cannot flow outward and lose contact with the stream, it becomes a stagnant pool; if the stream loses contact with the spring, which is its source, it dries up. Thus, “contemplation is the spring of living water, and action is the stream that flows out from it to others; it is the same water … this is the integrity of contemplation.”23 The spring and streams are inexhaustible. We therefore have no excuse. May we continue to learn by doing!

(Additional) Sources for further reading

Othering:

For an interdisciplinary analysis of “othering” drawn from four major areas: 1) peace and conflict studies, 2) psychoanalysis, 3) religious studies, and 4) interfaith dialogue literature, see Thomas Vincent Flores, “Encountering the Other through Interfaith Dialogue: A Constructive Look at a Praxis of Religious Identity and the Promotion of Peace” (Ph.D. diss., Emory University, 2006). See also Jay Rothman, Resolving Identity-based Conflict in Nations, Organizations, and Communities (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc., 1997).

Peacebuilding:

See Thomas Clough Daffern, “Peacemaking and Peacebuilding,” in Encyclopedia of Violence, Peace, & Conflict, ed. Lester R. Kurtz (Austin: Academic Press, 1999), 2:755; John Paul Lederach, Building Peace: Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies (Washington D.C.: United States Institute of Peace, 1997); John Paul Lederach, The Moral Imagination: The Art and Soul of Peacebuilding (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); John Paul Lederach, The Little Book of Conflict Transformation(Intercourse: Good Books, 2003), Preparing for Peace: Conflict Transformation Across Cultures (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1995); and Johan Galtung, Peace by Peaceful Means: Peace and Conflict, Development and Civilization (London: Sage Publications, 1996).

Spiritual nonviolence:

See all writings of Thich Nhat Hanh, especially, Creating True Peace: Ending Violence in Yourself, Your Family, Your community, and the World (New York: Free Press, 2003); Thomas Merton, Faith and Violence: Christian Teaching and Christian Practice(Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1968); all works by His Holiness the Dalai Lama; Cf. Pema Chodron, Practicing Peace in Times of War (Boston: Shambala Publications, 2006). See also all writing of Mohandas K. Gandhi, especially, Mohandas K. Gandhi, trans by Mahhadev Desai, Gandhi An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth (Boston: Beacon Press, 1993), The Essential Gandhi: An Anthology of his Life, Work, and Ideas, ed., Louis Fischer (New York: Vintage Books, 1962); andOn Nonviolence, ed., Thomas Merton (New York: New Directions, 1965).

Religious Violence and Peacebuilding:

See R. Scott Appleby, The Ambivalence of the Sacred: Religion, Violence, and Reconciliation (Maryland: Rowman & Littlefied Publishers Inc., 2000); Mark Jeurgensmeyer, Terror in the Mind of God: The Global Rise of Religious Violence (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003); Mark Jeurgensmeyer ed., Violence and the Sacred in the Modern World (London: Frank Cass & Co Ltd., 1992); and Charles Kimball, When Religion Becomes Evil: Five Warning Signs (San Francisco: HarperCollins, 2003). By Marc Gopin, see also Holy War, Holy Peace: How Religion Can Bring Peace to the Middle East (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002).

Examples of other continua of human relations:

See John Paul Lederach, Journey Toward Reconciliation (Scottdale: Herald Press, 1999), 47-49. See also Stephen Ryan, “Destructive Processes in Violent Ethnic Conflict,” in The Politics of Difference: Ethnic Premises in a World of Power, eds. Edwin N. Williamsen and Patrick McAllister (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 150-52. In relation to a continuum of tolerance within religious interrelations, see Leonard Swidler and Paul Mojzes eds., Attitudes of Religions and Ideologies Toward the Outsider: The Other (Lewiston: The Edward Mellen Press, 1990).

Contemplation:

There are of course volumes in this regard. The writings of the Desert Fathers constitute the classics, as well as classics by St. Teresa of Avila or St. John of the Cross. Some key contemporary texts might include: Fr. Thomas Merton, Contemplative Prayer(New York: Image Books, 1969), New Seeds of Contemplation (New York: New Directions Publishing House, 1972), The Inner Experience: Notes on Contemplation, ed. William H. Shannon (New York: HarperCollins, 2003), and Spiritual Direction and Meditation (Collegeville: The Liturgical Press, 1960); Fr. Thomas Keating, Open Mind, Open Heart: The Contemplative Dimension of the Gospel, Twentieth Anniversary Edition (New York: Continuum, 1986, 1992, 2006); Invitation to Love: The Way of Christian Contemplation (New York: Continuum, 1997); Fr. Richard Rohr, Everything Belongs: The Gift of Contemplative Prayer (New York: Crossroads, 1999).

Psychology and psychobiology of evolutionary human disconnection and hostility:

On the “naturally ingrained” self-other tension, the renowned developmental psychologist Erik Erikson coined the term “pseudo-speciation” (following the work of ethologist Konrad Lorenz) to refer to the natural tendency of all species, including humans, toward aggressive “affiliative bonding” mechanisms like the tendency to be drawn to and view one’s species or group as superior to all others. See Erik Erikson, Gandhi’s Truth: On the Origins of Militant Nonviolence (New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc., 1969), 431-434. Another prime example can be found in the work of psychiatrist Vamik Volkan, who speaks of the psychological “need to have enemies and allies” as well as the “natural” tendency toward adopting “suitable targets of externalization.” See Vamik Volkan, M.D., The Need to have enemies and Allies: From Clinical Practice to International Relationship (Northvale: Jason Aronson Inc., 1988). See also Aaron T. Beck, Prisoners of Hate: The Cognitive Basis of Anger, Hostility, and Violence (New York: Perennial, 1999). Beck’s appraisal regarding the development, processes, and functioning of the bio-psychological “primitive thinking apparatus” is corroborated by those who approach violence from a psycho-anthropological and psycho-evolutionary approach. See, for instance, Michael P. Ghiglieri, The Dark Side of Man: Tracing the Origins of Male Violence, (Cambridge: Perseus Books, 2000); Willard Gaylin, Hatred: The Psychological Descent into Violence (New York: BBS Public Affairs, 2003); Cf. also Richard W. Bloom and Nancy Dess, eds., Evolutionary Psychology and Violence: A Primer for Policymakers and Public Policy Advocates (Westport: Praeger, 2003). See also David Berreby, Us and Them: Understanding Your Tribal Mind (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2005).

Altruism, Empathy, and Prosocial behavior:

Staub has numerous works including earlier works such as Positive Social Behavior and Morality: Social and Personal Influences Vol. 1 (New York: Academic Press, 1978); and Positive Social Behavior and Morality: Socialization and Development Vol. 2 (New York: Academic Press, 1979). He has more recent works as well. See also, Lawrence Kohlberg, The Philosophy of Moral Development: The Nature and Validity of Moral Stages (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1984). For more contemporary studies, one could simply google the search terms: “empathy training and service work,” “altruism and service learning,” or “positive social behavior and service.” There are literally thousands of scholarly articles and studies, in addition to numerous reports from non-profit educational organizations supporting these connections. Finally, see Samuel P. Oliner and Pearl M. Oliner, The Altruistic Personality: Rescuers of Jews in Nazi Europe (New York: The Free Press, 1988). One can access more of their contemporary work at the Altruistic Personality and Prosocial Behavior Institute at Humbolt State University. See:http://www.humboldt.edu/altruism/index.html.

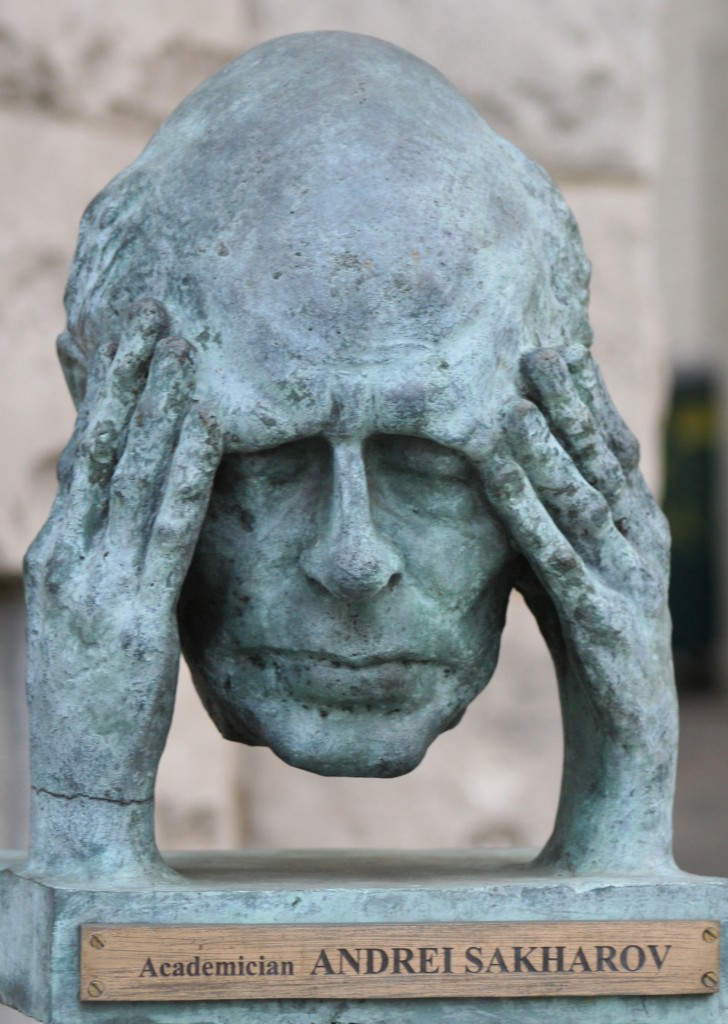

Photograph by dbking.

Notes

- See the UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization) Constitution, Section A. To view, go tohttp://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=3509&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html. The general consensus regarding the origin of this (Hindu) Vedic aphorism is that is derived from the Atharva Veda. The idea is certainly confirmed by other ancient Vedic texts, the Bhagavad Gita, and early Buddhist texts as well.

- Mark Juergensmeyer invented this term in his Terror in the Mind of God(Berkeley: University of California, 2001).

- My focus on certain of Ervin Staub’s concepts for this discussion are taken directly from his book with the same name, The Roots of Evil: the Origins of Genocide and Other Group Violence(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989). However, some of these same principles can be found in Ervin Staub, The Psychology of Good and Evil: Why Children, Adults, and Groups Help and Harm Others (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003); and,Overcoming Evil: Genocide, Violent Conflict, and Terrorism (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2011). Dr Staub is professor emeritus of psychology at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and Founding Director of its Ph.D. concentration in the Psychology of Peace and Violence. He has won numerous awards for his scholarly contributions to peace, conflict resolution, reconciliation, and justice. For an extensive list of his publications, See:http://www.ervinstaub.com.

- Staub’s theory of the continuum process is more nuanced than presented in our discussion. For a more detailed explanation, see Roots of Evil, 3-34. He has also applied this form of analysis to Rwanda in, for instance, Staub, E., Pearlman, L.A., and Miller, V., Healing the roots of genocide in Rwanda. Peace Review15:3, 287-294, 2003., or, Staub, E., “Promoting reconciliation after genocide and mass killing in Rwanda—and other post-conflict settings,” In Nadler, A., Malloy, T., and Fisher, J.D. (eds). The Social Psychology of Intergroup Reconciliation (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

- For example, this concept is unfortunately confirmed and illustrated in the first-hand account of a Rwandan genocide survivor, Immaculée Ilibagiza with Steve Erwin in, Left to Tell: Discovering God Amidst the Rwandan Holocaust(Carlsbad: Hay House, 2006). Another example is documented in the case of the former Yugoslavia within the Serbian context. See Chris Hedges, War Is a Force that Gives Us Meaning (New York: Anchor Books, 2002), 83-121.

- Staub, Roots of Evil, 4-34. For our purposes, “prosocial” refers to human attitudes, emotions, and behaviors that foster connection, friendship, goodwill, concern, respect, and affirmation of human dignity. There are no limits to prosocial expression.

- Ibid., 276-77.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 274-283.

- Staub does not directly name the exact same elements of the continuum of benevolence as I have in this diagram. He does however, explicitly refer to “caring” and “connection,” and the acquisition of “superordinate goals,” which are goals that are higher than the individual, shared by a group, and are not in conflict with aggressive survival goals. I have distilled and infer the other components from the entirety of the book in the transition from a continuum of destruction to one of benevolence. See ibid.

- See Thomas Merton, Contemplative Prayer (New York: Image Books, 1969), 34.

- See Fr. Richard Rohr, Everything Belongs: The Gift of Contemplative Prayer(New York: Crossroads, 1999).

Ibid.,19-104.- For example, see Merton, New Seeds of Contemplation; No Man is an Island (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1955), Raids on the Unspeakable(New Directions Publishing Corporation, 1964); see also Fr. Thomas Keating, Open Mind, Open Heart: The Contemplative Dimension of the Gospel, Twentieth Anniversary Edition; Invitation to Love: The Way of Christian Contemplation; Contemplative Prayer CD Audiobook (Boulder: Sounds True Incorporated, 2004); See, Henry Nouwen, ed. John Dear, The Road to Peace: Writings on Peace and Justice (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1998). See also, Richard Rohr and John Feister, Hope Against Darkness: The Transforming Vision of St. Francis in an Age of Anxiety (Cincinnati: St. Anthony Messenger Press, 2001).

- Ahimsais a Sanskrit word, the negation of the word himsa, meaning “desire, intent to harm.” However, it is more than just a negation (such as “nonviolence” or “non-harm”); it is a positive force in the other direction. Satyagraha is a Sanskrit conjunction of two words, “truth” and “force.” Gandhi proposed that the word be paraphrased by “soul force.” It literally means, “clinging to truth.” See Michael Nagler, Is There No Other Way: The Search for a Nonviolent Future (Berkeley: Berkeley Hills Books, 2001), 58-68. See also Nagler’s non-profit organization website for further definitions:http://www.mettacenter.org/nv/nonviolence/intro.

- Cited in Nagler, Is There No Other Way?, 97. Numerous Buddhist practices from a variety of lineages cultivate these virtues. These might generally be called “mindfulness/awareness,” “compassion,” or “loving kindness” meditations/practices. This might include (among many others) such concepts and practices as: “Tonglen” (a transformative method for connecting with our own suffering and that around us), “Bodhicitta” (the union of compassion and wisdom to benefit all sentient beings), or “Maitri” (the basis of compassion, or the perfect virtue of sympathy). One can find numerous interpretations of these concepts and other practices in the works of such figures as The Dalai Lama, the Vietnamese monk, Thich Nhat Hahn, as well as from contemporary Buddhist teacher in the Shambala tradition, Pëma Chodron. There are of course numerous other teachers from within the diverse canons of Buddhist teachings.

- SeeHis Holiness the Dalai Lama, Ethics for the New Millennium (New York: Riverhead Books, 1999).

- See Alcoholics Anonymous: The Story of How Many Thousands of Men and Women Have Recovered from Alcoholism, Third Edition(New York: Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, Inc., 1976), 84-87. See also Alcoholics Anonymous, Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions (New York: Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, Inc., 1981), 90-95. Of course the idea of a reflective inventory is not unique to Alcoholics Anonymous. In the 1500’s, Ignatius of Loyola advocated taking a nightly or even hourly moral inventory. His method differs from what we are advocating in that it was not intended as a spontaneous activity, but rather a ritualized form of prayer and meditation. See, St. Ignatius of Loyola, trans. Anthony Mottola, PhD., The Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius (New York: Double Day, 1989).

- There is no such verb form for the word “altruism.” However, because we are focused in this essay upon actions(verbs) rather than nouns and adjectives, I felt it permissible to create an appropriate “made up” word to convey a contemplative mental action. I beg the reader’s indulgence.

- This process does in fact work. Members of a long-standing interfaith dialogue group of Christians, Jews, and Muslims practiced a variation of these questions in their own interchanges with each other and outsiders. In fact, interviews with 12 members revealed that they practiced a form of the three-step process on their own. See Flores, Encountering the Other through Interfaith Dialogue: A Constructive Look at a Praxis of Religious Identity and the Promotion of Peace (Ph.D. diss., Emory University, 2006).

- Gopin, Between Eden and Armageddon, 84 (emphasis mine).

- Nagler, Is There No Other Way?, 222.

- Quoted in Thelma Hall, R.C., Too Deep for Words, Rediscovering Lectio Divina (Mahwah: Paulist Press, 1988), 10.