Download PDF: Varley

Introduction

To an increasing degree, ethnographic accounts of childbirth in South Asia examine how clinical facilities, and Labor Rooms in particular, operate at the interstices of mutually exclusive belief sets: one grounded in modes of authoritative knowledge and technical practice, the other reflected in modes of structured religiosity and issues of faith.1 As my recent research seeks to demonstrate, however, medical crises facilitate the alignment of these beliefs through shared attention to a common goal: in this case, the safe delivery of an infant and its mother’s survival. Through extended qualitative fieldwork in northern Pakistan, my research builds on anthropological analysis of the ways that “medical authority is constructed and asserted through the technologies of reproduction” to also explore how issues of religious identity and, more specifically, Islamic therapeutic resort arise within the domain of clinical service provision to alleviate risk, remedy harm, and attain well-being.2

Notwithstanding research analyzing the interplay between biomedical and traditional health paradigms throughout the developing world, the available literature continues to emphasize Labor Rooms as a site for biomedical hegemony and technological dominance, rather than identifying how religious identity and spiritual mediation can factor in patient-provider interactions. While recent research has paid significant attention to the ways that patient-provider relationships emerge from clinical encounters to reflect and reify social hierarchies, gender, economic status, and professional agency, the available literature often places an undeservedly minimal emphasis on the ways this relationship, particularly during moments of crisis, is shaped and imbued by shared belief in the remedial force exerted by prayer and religious intercession. With notable exceptions,3 ethnographic under-attention to the synthesis of religious beliefs with clinical maternal health services is particularly a problem for accounts of childbirth in the Muslim world. Accordingly, I attend to the discursive, symbolic, and material ways that patient-provider interactions reflect and reproduce those aspects of Islam that intersect with matters of health and survival.

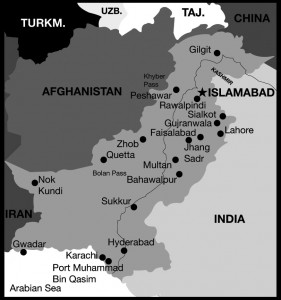

My fieldnotes detail the events surrounding an obstructed delivery in Gilgit Town, administrative capital of the semi-autonomous Gilgit-Baltistan region, at the height of the summertime floods that wreaked havoc throughout northern Pakistan and later affected southern portions of the country.4 At the same time that I attended this delivery case, flood-related service disruptions had seriously undermined local hospitals’ ability to provide safe delivery services. In the Labor Room of Gilgit Town’s District Headquarters Hospital (DHQ), the primary referral hospital for Gilgit-Baltistan’s 1.5 million residents, physicians, nurse-midwives, and Lady Health Visitors (LHVs)—a junior equivalent to nurses—attempted to balance the needs of routine and emergency delivery cases with profound resource deprivations. Women from across the socio-economic spectrum delivered at this site, regardless of the risks posed by its under-funded, under-resourced, and under-staffed services.5

The 2010 floods had seriously exacerbated the hazards normally associated with medical treatment at the DHQ. For several weeks following the worst of the flooding in late July, the Labor Room had gone without electricity and water. In the days immediately prior to this delivery, partial supplies of electricity and drinking water had been restored. The Labor Room remained in a dire state, however, thanks to the lack of water required to clean the facilities or sterilize instruments. And in ways that compounded the risks already posed by under-equipped and under-resourced settings, deliveries in the Labor Room were routinely conducted without the supervision of trained nurses or physicians. With physicians and senior nurses busy handling hundreds of patients at the DHQ’s Outpatient Department each day, Lady Health Visitors, who have minimal training in safe delivery techniques, were frequently left on their own to handle a wide array of regularly occurring childbirth complications. Such was the case the day I watched “Safeena,” a young woman from a mountain village east of Gilgit, attempt to deliver her first baby.”Entrance to DHQ Labour Room” by author.

In the four hours I observed Safeena’s case, I was struck by the apparently seamless integration of patient-centered Islamic invocations and family-generated remedial techniques with emergency obstetric service provision.6 When the DHQ’s Lady Health Visitors failed to alleviate the crisis or secure timely intervention by on-duty physicians, Safeena and her family turned to traditional Islamic practices for resolution. In Gilgit, intercessory prayer (dua) and the use of amulets (tawiz), ritual recitations (dhum) and invocations are regular components of patient- and family-centered Islamic resort during childbirth. In order to hasten delivery, patients and their families draw on a wide array of shared and sect-specific Qur’anic, Prophetic, lay, and localized forms of Islamic therapeutic intervention and knowledge.

Islamic recourse for childbirth-related crises is often standardized and employs commonly used remedial methods. Clerics (mullahs), however, make innovative use of existing texts and traditions to devise additional strategies. At no small expense and well in advance of delivery, families might procure amulets made of fabric, written squares of paper emblazoned with spidery Urdu script, or small bags of sugar on which recitations and prayers have been blown for the mother to eat. If labor is protracted and such measures are not at hand, women’s families will seek out clerics or other individuals possessing holy characteristics or healing skills to produce these items.

What complicates and enriches the available hierarchy of Islamic resort is Gilgit-Baltistan’s multi-sectarian composition. The region is characterized by ethnic and sectarian diversity, with Gilgit Town populated by equally sized communities of Sunni, Shia, and Ismaili Muslims. Sectarian-aligned beliefs and notions of identity are routinely introduced into clinical interactions, if only passively, by maternity patients. For instance, Shia women’s frequent use of the invocation “Ya Ali” (Oh Ali) and Sunnis’ preference for “Ya Allah” (O God) serve to index delivering mothers’ sectarian affiliation along with the different ways women appeal for divine intervention. For Shias, invocations of “Ya Ali” signal the mediatory power of the Caliph Hazrat Ali, son-in-law to the Prophet Mohammed and spiritual progenitor of the Shia sect. Specifically, Shias’ use of the word “Ya”—which in Arabic denotes omnipotence and omnipresence—before the Caliph Hazrat Ali’s name stands in stark contrast to Sunnis’ insistence that only Allah can be characterized in such terms.

The use of Islamic therapeutic resort during childbirth, then, is suggestive of or demonstrates religiosity and sectarian affiliation as well as uncertainty, anxiety, and the possibility of imminent harm. In this way, the practice of faith and Islamic resort have the potential to reflect women’s actual and perceived vulnerability to the dangers posed by childbirth in under-equipped clinical settings. Because the floods led to dramatic reductions in physicians’ supervisory capacity and further impaired the state of clinical sites and services, patients made comparatively greater use of Islamic resort in order to compensate for risks that were unresolved or worsened by the DHQ’s summertime conditions. As Comelles observes for families’ use of prayer in an acute care ward in Spain, while medical discourse reduces clinical events to discussions of what “happens,” the language and techniques of faith used by patients and their families actively resist fear and express hope (omeed).7

My observations of and reflections on this particular case raise a number of questions: How do emergency childbirth scenarios and the specter of loss underpin the strategic deployment of faith? How is maternity patients’ use of Islamic rituals and invocations representative of crisis-incurred spiritual recourse? How are languages of risk—one anchored in Islamic doctrine, the other in clinical sensibilities—employed during childbirth? Specifically, how do patients and their providers simultaneously employ Islamic and clinical measures to reduce risk and promote delivery? And, finally, in what ways is women’s use of specific invocations intended to emphasize urgency and subjective need in clinical settings that routinely and discursively disavow fear, liminality, and mortality?

Fieldnotes: August 16, 2010

In the early afternoon on August 16, I entered the Labor Room to see “Safeena” half sitting, half lying across the delivery bed wearing a dark, patterned cotton kameez (shirt), her black hair tousled and her eyes bleary and focusing only weakly on me as I came to her side and briefly rubbed her upper arm. I looked down at the floor beside the delivery table to see blood dripping slowly and steadily from an IV-line that had, after staff realized it had become backed up with her blood, been removed from Safeena’s arm and emptied onto the ground over one of her discarded shoes.

At that moment, the staff were busy helping to deliver another young woman who was pregnant with her first baby at the bed next to Safeena’s. Because the expectant mother wasn’t shifting quickly enough down to the end of the bed to deliver, the staff—LHVs, dayahs, and trainee midwives—were having to wrestle and push the patient, who was crying out in pain all the while, into a position where “Aliya,” the on-duty LHV, could perform an episiotomy and then catch the baby boy as he fell—very quickly—into her hands.

In between deliveries, the on-duty dayah had only been able to make occasional trips to collect water in plastic buckets from a small reserve cistern behind the DHQ’s Family Wing. Thanks to her efforts, and armed with a mop-head swinging from a long, ratty rope, an ayah (female hospital orderly) was able to come into the Labor Room and started swinging a wet mop from side-to-side across the floor while Safeena lay back, straining with the effort to deliver. Despite the ayah’s best efforts, the room still smelled of blood, sweat, and filth, and the floor was now streaked lightly with blood and water. Suddenly the power cut and the room was now dank and dim. With no available water and only infrequent and weak supplies of electricity, the hospital’s Labor Room was still in a poor condition nearly three weeks after the initial, heavy flooding of late July. Spatters of old and fresh blood could be seen all across the floor. Without electricity, the Labor Room’s one autoclave (sterilizer) was not working and delivery instruments were being bathed in a small pan of Biodine. In the adjacent Outpatient Department, physicians were overwhelmed by a surge of patients sickened by water contaminated by the floods and were, as a result, largely unable to attend to delivery patients. Due to shortages in essential and emergency medicines at the hospital, patients were forced to purchase necessary drugs from local dispensaries. Cold storage for many medications and vaccines had been discontinued. The bathroom could not be used due to a lack of water, and the sheets on beds in the pre- and post-partum patient rooms were heavily stained. Nothing had been washed or changed in over a week. The smell and heat that greeted me at the main entrance to the Labor Room left me nauseous and light-headed.

With the other patient’s baby safely born and the mother moved, walking weakly and leaning heavily against a trainee midwife and her sister-in-law’s arms, to the recovery room, the staff returned their attention again to Safeena, who had been pushing for three hours by the time I entered the Labor Room.

On the middle of three delivery tables, Safeena lay back with her eyes staring blankly, her mouth opening and closing like a fish as she tried to catch her breath in the dark and still room. They kept urging her to “sahns lao” (take a breath) while Aliya, who handled much of the case, demonstrated. Aliya and two other LHVs alternately took turns stretching open the vaginal canal as they shouted at Safeena to push with all her might. In between Safeena’s weak and infrequent contractions, Aliya would occasionally wipe at her face with a sleeve, after first checking it to make sure there was no blood spatter on the sleeve. Or, she would ask a trainee midwife to wipe her face. In the thick heat of the room, Aliya’s face was covered in sweat, her thick black hair curling at the nape of her neck, from the effort of trying to deliver the baby.

After an hour of actively encouraging, cajoling, and shouting in frustration at Safeena to push, and with one LHV and dayahsitting beside her on the delivery table, their hands on her belly to check if she was beginning a contraction and could then push, it was clear that her labor was dangerously slow and not progressing. Aliya told me she’d already had problems finding the baby’s heartbeat during contractions earlier in the day. The level of anxiety evident among the staff and Safeena began to increase. After declaring that they would have to wait until the on-duty physician—who’d just been called from her private practice to return to the hospital and assist with Safeena’s case—Aliya instructed Safeena to lie and rest on her left side. Safeena shifted over, and Aliya, by placing a hand over Safeena’s, showed her how to rest her hand on the side of her right thigh. Aliya then took a wad of cotton gauze and began wiping the blood off Safeena’s legs and feet.

With tears rolling down her cheeks, Safeena cried, “Mey aj’et ho teht” (Call my mother). One of the LHVs went to the main hallway outside the delivery room, where Safeena’s worried and teary-eyed mother, a woman in her sixties, stood with hands outstretched in supplication (dua), silently mouthing prayers, and awaiting news of her daughter. Safeena’s mother came into the room and, on the advice of the LHV, urged her daughter to push as hard as she could, to appreciate the efforts made by all the staff attending her, and to try again—with all her might—as it would only take one or two more pushes and the baby would be born. Her daughter cried out in pain and reached a hand out for her mother to clasp, but the LHVs asked her mother to leave the room once again so they could return their concentration to Safeena.

Suddenly, Safeena’s contractions intensified in strength and duration. Aliya urged her to roll back onto her back and to start pushing again, but after a few pushes it seemed once again to be to no avail. Safeena’s mother re-entered the room with a handful of sugar in her hands, over which a prayer (dhum tee’toh shukr) to speed up delivery had been recited and blown. Half the sugar was poured into Safeena’s open mouth; her mother kept the remainder in her hands. Safeena called weakly for water. A trainee midwife brought a plastic bottle half-filled with muddy water—contaminated after the floods—from which Safeena took a few sips.

Several minutes later, the mother reappeared at the door to the Labor Room, holding a long strip of velvet fabric in which had been tied a knot. Underneath the knot, a dhum (prayer) had been blown and then the knot made to “secure” and “fasten” the prayer to the material. Against Safeena’s weak protests, this was tied onto her left thigh by a dayah. A trainee midwife pointed out to me that Safeena already wore another tawiz (amulet), wrapped in white cotton and tied onto her upper right arm. Every effort—spiritual and medical—was being deployed to help her deliver safely. Each of the Islamic measures used to assist Safeena were described as being particularly “potent” because, either by resting against her skin or being imbibed, they had the potential to affect her with greater speed and strength than the prayers offered by others. Indeed, with formal prayers (namaz) forbidden to her during childbirth because she was in an impure state, it was left to Safeena’s family to perform namazand intercessory prayers (dua) on her behalf as they waited in the hallway outside. According to my participants, the Qur’an and Hadith Al-Sunnat endorse a number of prayers specifically to help women during labor. If the pains were severe, for instance, patients’ families could perform two rakat nufl in namaz.8

Despite being unable to pray, Safeena was not restricted from invoking God’s name.9 As transcribed Labor Room discussions attest, exchanges between Safeena and attending LHVs were characterized either by her appeals to Allah for help or by the LHVs’ increasingly panicked exhortations for her to try, against the odds, to deliver her baby. The silences normally demanded by family and health care providers of delivering mothers in Gilgit were, in this case, not enforced.

“Push it down!” one LHV shouted. “Teht, teht, teht! Do it, do it, do it!”

The mother, her face glistening with sweat, shook her head lightly from where she lay on the bloodied delivery table, saying, “What can I do? It’s not coming. . . . wa y’Allah, y’Allah! Oh God, oh God!”

An older LHV leaned towards Safeena, saying, “Ouhn tey! Push it out! Move it a little bit down.” “Do it, do it, do it!” added the younger LHV, who stood at the foot of the table, her hands on her hips. “Try to get it a little bit down,” the older LHV encouraged again.

Safeena pushed, groaning lightly, only to give up and sigh in exasperation. In a voice weakened by exhaustion, she said to the two LHVs, “Nay bin, it’s not happening. Wa y’Allah! Come, oh God! Nay bin . . . oh God, it’s not happening! It’s not coming down. . . . What should I do? Wa y’Allah! Come, oh God! What should I do? I’m dying. . . .”

The older LHV turned to the younger LHV at her side, saying quietly, “And we’re just at the beginning.”

Upon hearing the LHVs discussing her case, Safeena added again, “Wa y’Allah! Y’allah. . . . It’s not coming down from inside. What should I do? Y’allah . . . wa y’allah. Enough, get me up. . . . I’m dying. Get me up. . . . y’Allah. Y’allah Khoda . . . y’allah Khoda . . . oh God, God . . . y’allah Khoda.”

The older LHV asked of a lay-midwife standing at the door separating the Labor Room from the main hallway, “Call her mother. Where did she go?”

Meanwhile, Safeena’s quiet invocations and pleas continued: “Wei y’Allah . . . pain, oh God. . . . What can I do? What can I do? I’m dying. Wei y’Allah . . . y’Allah, y’Allah!”10

Several minutes later and with no progress made even despite Safeena’s best attempts, the LHVs began encouraging her again to push: “Shaht tah wah . . . do it harder!”

Safeena’s contractions were erratic and weak. She was well aware of her predicament, and her exhaustion had shifted into a quiet fatalism. “Sit me up, I can’t do it. . . . It’s too much.”

“You shouldn’t have come from your home if you didn’t want to do this, right?” the older LHV retorted in a sharp tone.

In response, Safeena tried to push once again: “Y’Allah!”

“Do it! Do it!” the younger LHV shouted.

“Meh shom shuhkeen . . . my mouth is dry,” Safeena moaned. “It’s not coming down . . . kitih na wan.”

“Kitih wa’leh! Push it down! Push it down! Push it down!” the younger LHV shouted. “Do it, do it, do it!”

“Nay bin, li . . . it’s not happening,” Safeena answered after another short contraction. “Mas jek tham, me marianas . . . what should I do? I’m dying.”

Without a pause, the two LHVs shouted in tandem: “Do it, do it! Do it, do it, do it, do it, do it!” and “Shaht tah wah . . . try harder! Do it harder!” Safeena, her face a mask of pain, answered in a resigned voice, “Come, sit me up. . . . It’s too much for me.”

With the arrival of another brief contraction several minutes later, the LHVs continued their refrain of “Do it! Do it! Do it!” Safeena countered once again with, “Wah nah behn . . . it’s not coming. . . . What should I do?”

The older LHV, slapping a hand to her head in frustration, shouted, “Y’Allah! Oh God! Wah, li! Come on, girl! Deh, deh, deh! Give, give, give! Deh, li! Give it, girl! Wah toh wah toh . . . it’s coming, push it!” Safeena pushed, the veins standing out against her neck and forehead.

The younger LHV tried to encourage her, saying “It’s coming down!” From the faces of the lay-midwives standing at the foot of the delivery table, I could see this wasn’t true.

Safeena began to give up. “Wa y’Allah, it’s not coming down. . . . No, it’s not coming. I’m dying.”

“No,” countered the older LHV. “It’s coming out!”

“No, it’s not coming,” answered Safeena. “Wah . . . ney nikahn nah. Oh . . . it’s not coming out. Wa y’Allah, wa y’Allah . . . you’re killing me, you know. . . . Wei y’Allah, y’Allah! Pain, oh God, oh God! Mas jek tham, nah? What should I do? Wei y’Allah . . . pain, oh God!”

“Have courage!” the older LHV pleaded. “It will happen if you have some courage. . . . Do it, do it, do it!”

“Wah nay bin . . . It’s not coming. Y’Allah, y’Allah . . . A’li, mas jek tham? What should I do? What should I do?”

Moments later, after another futile attempt to push the baby down, Safeena began to moan, tears falling onto the pillow: “Y’Allah . . . y’Allah . . . wei y’Allah . . . I’m dying. Bas, hoon tah. Enough, get me up. . . . I’m dying.” Then, “I’m having difficulty, get away from me. . . .”

The older LHV, her patience nearly finished and her anxiety now obvious, responded to Safeena’s tears by saying sharply, “If you have a brain in your head, if you have humanity, you will do it. . . . You can do it! If a person wants to do it, with full concentration, determination—from your head—go do it! You’re going to get worse if you don’t pay full attention.”

In a quiet voice, Safeena said, “My stomach hurts. . . . What can I do?” Laying her hand on Safeena’s upper thigh, the LHV responded, “Yes, there’s pain. It will hurt. But you have to do it.” Encouraged, Safeena began to push again but soon gave up as the short contraction wore away. “Y’Allah . . . y’Allah . . . It’s not coming, what should I do? Wa y’Allah, mas jek tham, la? What should I do?” And in a rising voice: “Y’Allah . . . y’Allah . . . y’Allah . . . y’Allah, y’Allah.”

Near the end, very clearly and seemingly without pain, Safeena told the LHVs, “Leave it. Just stop it. I can’t get the baby down—I’m going to die.” People didn’t say much, and the mood was grim. In response to Safeena’s gently spoken protests that their efforts weren’t helping and she was dying, one LHV said, “If you have the breath to say that, you can focus on pushing.” The LHVs alternated between cajoling her and yelling at her. Meanwhile, one dayah and one LHV were sitting beside her on the bed, plucking at her belly perhaps to stimulate a contraction or to test whether she was having pains. The four trainee midwives were obviously unsettled by the whole process. One young trainee midwife, wearing glasses and with her hair pulled back into a ponytail, went and sat heavily on the vacant delivery table beside Safeena’s, a hand to her forehead. Looking at me with a weak smile, she explained she was exhausted and dizzy. Despite their apprehension and obvious fear, the trainee midwives were conscientious about caring for Safeena throughout the delivery—rubbing her forehead, holding up her head as she pushed, and fanning her off between contractions with a sheaf of papers.

For the next forty minutes, Aliya and the other two attending LHVs were visibly sweating from the effort of exhorting her to push. Almost without pause during each contraction, they shouted “Zor sey” (with strength), “zor lugao” (strike hard, try hard), and “teht, teht, teht” (do it!). The younger LHV was almost spitting as she yelled. The older LHV began to sigh loudly over and over. There were periods of intense activity and then quiet calm when attending staff sat or stood by, exhausted and uncertain. There were also moments when, verging on panic, the LHVs debated what to do or discussed the possibility that the baby or patient might die, seemingly oblivious to the patient’s presence. Safeena remained silent, blinking weakly, occasionally saying to the LHVs at her side, “Leave me be; it’s no use.”

On two different occasions, Safeena’s mother brought in two small plastic containers of oil bought from nearby dispensaries because the Labor Room’s daily supplies had been used up. The oil was squirted into a small bowl and then poured over the vagina as the LHVs did exams and tried to help deliver the baby. After each examination, deep red clotted blood spilled out onto the metal tray and slid slowly into a stainless steel bowl placed at the end of the delivery table.

Safeena’s pains were infrequent and short in duration and strength. She would push, but only for a few seconds with gritted teeth. At the beginning of my observation, the LHVs told me that they had been unable to hear the baby’s heartbeat during contractions earlier in the day. Later, as I watched, the older LHV found the heartbeat again and solemnly proclaimed that the baby was “in distress.” After this, they were vigilant about regularly checking the heart beat with the fetascope between contractions. The electronic fetal monitor was missing its battery. Aliya would place a handful of gauze over the mother’s vagina as she leaned in closely to listen just above Safeena’s pelvic bone.

At one point, the younger LHV strode out of the Labor Room and at the patient registration desk scribbled a note in a ledger book. Over her shoulder, I read that a call had been put in to an on-call doctor requesting immediate help for an obstructed labor with a ‘PG’ (primae gravida, first delivery) patient. Passing it over to a dayah, she yelled, “As fast as you can run, that fast you should go!” and sent the dayah to the hospital’s supervising physicians in the main patient block a few blocks away. Despite the LHV’s plea to hurry, the woman simply dawdled off. The Labor Room’s one phone, which staff and physicians normally used to call for help, was out of order. So, each time staff tried to contact the on-duty physician to come and attend the case, an LHV held her own cell phone to Aliya’s head as she spoke. Aliya was unable to hold the phone herself as her hands were encased in plastic gloves and coated with blood.

When the Labor Room door opened, I could see Safeena’s family members looking in the room to try to see what was happening. Other patients and their attending relatives could easily hear Safeena’s cries. There was grim curiosity over this difficult case. All the while my research partner, Nur-ul-Ain, was busy calling the Amphari Mohalla (neighbourhood) sub-station for power to be directed to the DHQ. Although during regular periods of “load-shedding” the DHQ ordinarily had electricity supplied to it by a full-time “special line”—reserved to ensure the functioning of government offices and the DHQ—the “special line” was no longer functioning. The one generator that had been provided to supply auxiliary power to the Operation Theater on the floor above the Labor Room had gone missing. Thanks to Nur-ul-Ain’s efforts, and only two minutes before the baby was delivered, the power came back on “full.” The lights seemed extraordinarily bright, and the overhead fans spun like helicopter blades. Almost immediately afterwards, the baby began to crown after many hours worth of effort.

At precisely the same time, the on-duty physician hustled into the Labor Room. Extremely pale after being sickened by flood-contaminated drinking water, she got immediately to work, taking off her doctor’s coat and passing it to an LHV. As soon as the power had come on, everyone rushed to prepare the Labor Room equipment. The vacuum took some time to assemble and turn on. Aliya and the older LHV struggled to figure out how to securely fasten shut the vacuum container lid, while anotherdayah set up the infant oxygen and suction machines near the infant warmer.

While whispering “Bismillah” (in the name of God), an invocation that marks the start of any effort or event, under her breath, the doctor pulled on latex surgical gloves and instructed a trainee midwife to reattach the cannula and ensure that glucose was moving quickly into the mother through the drip. The doctor’s tone was initially very encouraging as she spoke to Safeena, who was totally exhausted at this point. When she realized the baby was truly stuck, her tone shifted to forceful and strong, as the LHVs’ had been before she arrived. She called for a surgical apron while Aliya unwrapped the doctor’s dupatta (veil) from around her neck and put it aside. Another LHV then came over to tie up the doctor’s apron at the back. The doctor also asked for a pair of boots to protect herself against blood and fluid. Two pairs of purple ankle-high boots were always kept at-the-ready on the side of the Labor Room.

Without having time to administer local anesthetic, the doctor performed an episiotomy. Safeena, wan and listless, appeared not to notice. At the same time, Aliya and the older LHV were busy preparing the vacuum to help extract the baby’s head. Once it was attached to the baby’s exposed crown, the doctor, with her hand resting atop Safeena’s belly, instructed Aliya to only begin pulling during a contraction. While one of the LHVs plucked lightly at Safeena’s belly to feel how taut it was, they waited until a contraction came and then started pulling hard. The mother pushed, her teeth gritted and groaning deeply. As the baby’s head, covered in black hair, emerged, the doctor reached to catch its arm and pulled very hard, saying “Bismillah, bismillah, bismillah” many times in row.

After being completely delivered, the baby was hung by its feet in the hands of an LHV. Its body was purplish. I caught only a glimpse of the baby’s face, her mouth opening and closing silently, before she was rushed over to the infant warmer where the doctor and Aliya took turns suctioning her airways. The baby made only one very weak cry in the initial twenty minutes after being delivered. The doctor worked hard to resuscitate the baby while an LHV did stitched up Safeena, who was crying out from pain. The doctor massaged the baby’s chest, doing chest compressions. The baby soon pinked up, although she was not blinking her eyes or crying. Another on-duty physician rushed in at this time and took over the baby’s resuscitation. In between bouts of chest compression, she gripped the baby’s ankles and briefly hung her upside down, thumping at her back.

I gestured to Aliya to tell me how the baby was doing. She mouthed the word “zaya” (lost), but the younger LHV, noticing us, called over to say she thought the baby was “ok.” The two physicians then wrapped up the baby in a receiving blanket provided by a family member. The baby girl now had an oxygen mask over her face, but she remained unblinking. And when she breathed, her mouth opened wide with the effort.

Safeena’s family was still waiting outside in the hallway. No one had told them that the baby had been delivered yet, and their distress was palpable. Her mother was accompanied by three other younger women relatives. One of the nurses opened the door briefly to tell them that the baby was born but unwell. Nur-ul-Ain, who stayed with Safeena’s family in the hall, later told me that the mother began weeping upon hearing the news. And yet she immediately stretched her hands out before her in a gesture of supplication (dua), murmuring “Shukr al’hamdillilah” (thanks to God), regardless of her newborn granddaughter’s poor condition. The delivery was over, the mother was alive, and there was still the chance the baby might survive.

One of the doctors called for a Specialist Physician to come from the Child Ward in the main patient block, some distance away from the Labor Room. He arrived in the hospital’s one working ambulance five minutes later and stood outside the Labor Room, holding an intubator and breathing tube in a sterile pack, waiting for the baby to be brought to him. After sitting on a bed in the LHVs’ off-duty room, the doctor checked the baby, who was pink but unresponsive. She wasn’t moving or crying; her eyes were still half-opened and unblinking. After listening to her heartbeat, he instructed a dayah to wrap the baby up and follow him to the ambulance, which would drive them the short distance to the DHQ’s equally under-resourced neonatal intensive care unit. After swaddling the baby, who had yet to begin crying, the dayah and a trainee midwife walked with the doctor to the waiting ambulance.

As soon as the Child Specialist left with the baby and Safeena’s episiotomy wound had been stitched, the two on-call doctors left. One went to attend to other DHQ patients, while the other returned to her private clinic.

Two days later I returned to the Labor Room, hoping to hear good news about Safeena and her daughter. While standing beside the bed of another delivering patient, the room once again dark and stifling without power, an on-duty LHV told me that the baby girl had died the next day in the Child Ward. She had no news of the mother, who had been discharged the day of delivery and taken home by her family, where she buried her daughter the next day.

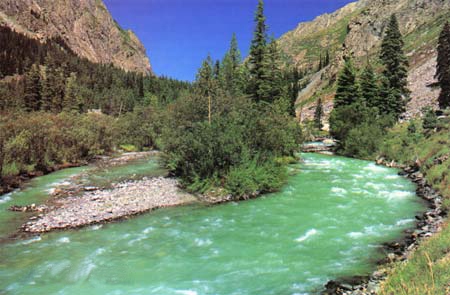

Photo: “River Swat, Kalam” by Farooq. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Notes

- See H. Donner, “The Place of Birth: Childbearing and Kinship in Calcutta Middle-Class Families,” Medical Anthropology22 (2003): 303-341; P. Jeffery and R. Jeffrey, “Only when the boat has started sinking: A maternal death in rural north India,” Social Science & Medicine 71 (2010): 1711-1718; Sarah Pinto,Where There Is No Midwife: Birth and Loss in Rural India (London: Berghahn Books, 2008); and Cecilia Van Hollen, Birth on the Threshold: Childbirth and Modernity in South India (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003).

- Maya Unnithan-Kumar, “Introduction: Reproductive Agency, Medicine, and the State.” In Reproductive Agency, Medicine, and the State: Cultural Transformations in Childbearing, ed. Maya Unnithan-Kumar (New York: Berghahn Books, 2004), 8.

- A. El-Nemer, S. Downe, and N. Small, “‘She would help me from the heart’: An ethnography of Egyptian women in Labor,” Social Science & Medicine62 (2006): 86.

- Portions of these fieldnotes were used by Brian Walker in his journalistic account of the floods’ impacts for Gilgit’s health services (http://ac360.blogs.cnn.com/2010/08/25/pakistan-hospital-cut-off-by-floods-struggles-to-help-survivors/). My fieldnotes have been edited in order to protect participants’ anonymity, confidentiality, and various details specific to the delivery case and clinical service provision.

- Although my research focused on Gilgiti Sunni women’s maternal health—see E. Varley, “Targeted doctors, missing patients: Obstetric health services and sectarian conflict in northern Pakistan,” Social Science & Medicine70 (2010): 61-70—my observations of labor and delivery involved patients from all sectarian communities.

- See Mohammad Tariqur Rahman, Reeza Nazer, Lindsay Brown, Ibrahim Shogar, and Anke Iman Bouzenita. “Therapeutic Interventions: an Islamic Perspective,” The Journal of the Islamic Medical Association of North America40 (2008): 60-68. In ways that demonstrate the influence of Islamist missionization in northern Pakistan and “modern” Deobandi Muslim clerics’ support of clinical biomedicine in particular, Sunni participants readily opined that the metaphysical “Islamic medical model is . . . open to forms of strategy as developed within other models” (Ibid., 67). This view was shared by women’s treating physicians who, as practicing Muslims from all sectarian backgrounds, upheld and affirmed the “spiritual, psychological, and material” merits of Islamic therapeutic resort (Ibid., 60).

- Josep M. Comelles, “Medicine, magic and religion in a hospital ward. An anthropologist as patient,” Rivista della Società Italiana di Antropologia Medica13-14 (2002): 273-274.

- Rakat nuflare voluntary sets of prayer prostrations that may be done in someone’s name or on their behalf. These are different from the rakat (prayer sets, prostrations) that form an obligatory (farz) component of the regular namaz. While rakat nufl are derived from both the Qur’an and Hadith Al-Sunnat, many participants characterized rakat nufl from the Sunnat as more “effective” than those derived from the Qur’an.

- Safeena’s own sectarian affiliation was ambiguous. Although she came from a Shia-dominated village, her invocations were commonly used by patients from each of Gilgit-Baltistan’s Shia, Sunni ,and Ismaili communities.

- ‘Wei’ should be noted/designated as a representative term for ‘pain’ in the Shina language.