Download PDF: Whitmore, Genocide or Just Another

Editor’s Note (December 22, 2010): Dr. Todd Whitmore of the University of Notre Dame published his peer-reviewed article “‘If They Kill Us, At Least Others Will Have More Time to Get Away’: The Ethics of Risk in Ethnographic Practice” in our most recent issue (issue 3, spring 2010). In that article, Dr. Whitmore develops a theological framing of ethnography as both a research method and an ethical practice. Since the publication of “If They Kill Us,” Dr. Whitmore has been in conversation with Practical Matters about the publication of documents, dating from the 1980s, that he received while doing research in Northern Uganda (available at musevenimemo.org). These documents attribute to the sitting President of Uganda, Yoweri Museveni, the intent to commit acts of genocide against the Acholi people, an ethnic group situated in Northern Uganda, as early as the 1980s.

Over the summer of 2010, Practical Matters undertook an academic review process, which included experts in Ugandan history and politics, to evaluate both the authenticity of these documents and the ethical implications of publishing them. While the reviewers generally supported the journal in a decision to publish the documents, Practical Matters decided that it is not the most appropriate medium in which to make these documents available. Practical Matters, the journal’s editors and advisors concluded, cannot adequately contribute to securing the safety of persons in Uganda who might face retaliation as a result of the publication of these documents.

The journal did, however, decide to publish Whitmore’s analysis of these documents, which is available here. In this piece, Whitmore examines the historical and political situation in Northern Uganda that, he thinks, renders the documents’ purported provenance and authenticity likely. He also explores the ethical implications of publishing them in an online format. The editors and advisors of Practical Matters feel that it is important to provide Whitmore a public context in which to practice the ethic he prescribes in “If They Kill Us.”

Readers who wish to send me their comments can do so to musevenimemo@gmail.com.

- Introduction

- Part I: The Interpretive Context of Intrigue

- Part II: The Authenticity of the Document: Policy Shifts, Land, Language, and Names

- Part III: The Implications of the Document: Genocide

- Concluding Remarks

With the immediate and remote contexts of the document set out, it is now possible to examine its contents with a view to further ascertaining its authenticity. I will focus on four key areas in my assessment: 1) the shift in policy by Museveni to include the colonially demarcated region of northern Uganda as part of the new Uganda; 2) Museveni and his brother Salim Saleh’s efforts—as predicted in the memo—to take possession of land in northern Uganda; 3) the consistency of the language of the memo referring to the Acholi as “backwards” and as “Chimpanzees” and “Monkeys” with public statements Museveni has made about the Acholi; and 4) the consistency of the names mentioned in the memo, including the code names for Museveni and Saleh, with historical events.

An Early Change in Policy

The memo, written on a typewriter, is dated November 14, 1986. I have tried to find documentation either confirming or contradicting the author’s claim in the memo of having taken a flight over northern Uganda from Arua to Gulu during the time described. Mention of the flight would be evidence of the document’s authenticity; mention of Museveni being out of the country at the time, for instance, would be evidence of inauthenticity. Thus far, I have not been able to find public documentation either way. This is not surprising given that it is not the sort of flight that would typically be covered in the newspapers of the time. It is worth noting, however, that less than a year-and-a-half later—April 5, 1988—the indicated recipient of the memo, Salim Saleh, Museveni’s brother and a Major General in Museveni’s army, conducted his own flyover, and similarly commented, this time on the record to reporters, “What do you think of this unpopulated place? Couldn’t it be utilized for growing food, cash crops, and ranching to improve our economy, being such a fertile area?”1 The million-plus Acholi in the region did not count as a human population. The title of the memo, “Subject: RETHINK,” suggests that the author is considering a change in policy plans. The author and the recipient had made a “hasty decision to draw another national boundary, which would exclude the backward northerners from our new Uganda, particularly the Chimpanzees called Acholis.” The flyover convinced the author that this previous policy was not wise. “I have now realized that the Monkeys called Acholis are sitting upon Gold Mine. It is surprising that even the British Colonialists did not make them utilize the rich land properly.” Consequently, a policy change is necessary: “I have now reversed our decision to expel them, with their lands, from Uganda. We must keep Uganda as the British left it. But we must assume full control of the fertile lands.” Like with the flyover, I have not been able to find written documentation with regard to the earliest NRM policy. I have, however, spoken both to an Acholi elder and to a former high-ranking official in the NRM who have knowledge of the period, and they both confirmed the change in policy. It might be objected that the memo cannot be authentic because Museveni at the time was a nationalist who was trying to unite the country after a five-year bush war and that he would not have given up the Acholi lands. However, if Museveni’s objective was a united Uganda, he had the opportunity to realize the objective before he seized Kampala. Museveni did not overthrow Obote; rather Tito Lutwa Okello and his brother Bazilio Olara-Okello—both Acholis—did. After the coup, Tito became President, and it was he who tried to unify the country by extending offers of peace to the remaining rebel groups. The efforts led to the Nairobi Agreement between the Tito Okello government and the NRA in December 2005. Elijah Dickens Mushemeza writes,

On assuming power in 1985, General Tito Okello Lutwa invited all fighting groups, including the NRA, to join together and form a united government in the spirit of reconciliation and nation building. The NRA did not respond, and this led to Tito Okello’s Government seeking a negotiated political settlement with the NRA. This resulted in the Nairobi Peace Agreement (17 December 1985), detailing power sharing arrangements and the composition of the Military Council. All parties also agreed to a ceasefire within forty-eight hours including the UNLA and the NRA.2

Instead of pursuing a united Uganda, Museveni used the time granted by the Agreement to build up his own army, and a month later he seized the capitol. These are not the actions of a leader seeking to unite a country. The use of the term “nationalist” to apply to Museveni, then, is an odd one if we are to pay attention to his actions rather than his rhetoric. With regard to initially redrawing the border to exclude the Acholi even though this would be to give up territory, the move makes sense if the land were as barren as he first thought it was and the Acholi were as “backwards” as he has repeatedly described them. Museveni, as we will see, is a theorist of social evolution and an advocate of modernization. The Acholi would be a drag on his new industrializing economy. As it turns out, he has developed that economy while leaving out northern Uganda—the poorest region in the country, with 42.6% of the population living on less than $1 a day3 —in any case. Moreover, as we will see later on in this article with regard to NRM/UPDF action in the Democratic Republic of Congo, state boundaries are no barrier to exploitation. Museveni has gone—as the memo indicates he would—wherever he thought that he could draw financial benefit. What drew his attention back to northern Uganda was the possibility of the production of wealth (under his control) through industrialized farming in the North. To the extent that Museveni was the nationalist he advertised himself to be, then, he did not consider the people of northern Uganda in general and the Acholi people in particular to be part of the nation. For Museveni, where the geographical boundary was drawn by the colonialists was a secondary issue to that of which ethnic groups would be participants in the new nation. This is a point to which I will return, but for now it is sufficient to point out that the contradictions built into Museveni’s presumed nationalism are not dissimilar to the contradiction in earlier stages of United States political history between the claim that “all men are created equal” and the reality of the exclusion of African-Americans from participation in governance. Whether or not the latter are within the nation-state’s geographical boundaries, they are not considered part of the nation.

The Scramble for Acholiland

As described in the memo, the shift to the later policy by Museveni is due to the wealth of land in northern Uganda and the President’s desire to control it. Here, there is abundant evidence for the memo’s account, and it is therefore the second area of my focus on the question of the authenticity of the memo. To interpret that evidence, it is necessary to understand the role of land in the Acholi culture of northern Uganda. The cultivation of land is the primary source of wealth-generating production, and thus livelihood, in northern Uganda. The vast majority of Acholi are rural-dwelling small-scale farmers. They often supplement their diet with game procured through hunting.4 The land available for these activities is, for the far greater part, held in customary ownership. That is to say, ownership, even when it is individual ownership, is not conferred via government-authorized written title but rather through oral mechanisms of clan authority. Even when an individual—or more precisely, an individual family—holds claim to a parcel of land, the controlling idea is that it is held ultimately for the common good of the clan. One important study puts the matter this way:

The land which a family owns is not considered as being totally “theirs”: it is their heritage and the future heritage of their children. Since they see that a family exists only as a part of a wider community, so its land is held within the wider structure of a community (clan) and as clan’s land. Land is the fundamental productive asset, without which one cannot survive, and so one’s social obligations and claims are intimately connected to claims and rights over land. These obligations extend to the next generation: land must therefore be protected for them, and if anyone who leaves the village and fails to survive in the urban economy, the customary land is a safety net, because they can always return and be allocated a plot. Land is also the link with people’s heritage—quite literally, since it is on the family land that one is buried.5

Hunting lands (tim) and grazing lands (olet) are held in trust by the clan as a whole. These are not empty lands; rather their purposes are best stewarded through allowing multiple families to make use of them whole rather than as divided up into smaller parcels. The fact that ownership is orally-based and dependent upon the memories of the persons involved makes customary ownership, particularly but not solely of the hunting and grazing lands, vulnerable in crisis situations such as the twenty-year conflict in northern Uganda.

On September 27, 1996, Museveni issued the mandate that all people in the Gulu district of the Acholi region move immediately to designated Internally Displaced Persons camps. The decision to displace the people into camps was by fiat. When Acholi MPs found out about the plan, they protested; Museveni then promised to re-consult with the military and to get back to the MPs in two weeks. He never did. It is noteworthy that it was Saleh who gave the reason for Museveni’s not doing so, pointing up the tight relationship between him and Museveni: no consulting took place because Museveni and Saleh “suspected bureaucracy and politicking over the issue.” That is to say, they were concerned about resistance to and perhaps defeat of their plan of forced displacement should the issue go to Parliament.6 When individual people refused to move to the camps, the soldiers beat them; when whole villages refused, the UPDF often used attack helicopters against their inhabitants. A report from the Acholi Religious Leaders Peace Initiative is worth quoting at length.

In every camp we visited in Gulu, people told us invariably that they were forced. In some cases people remember that soldiers gave them a seven-day deadline (Opit) or only three days (Awac), threatening to treat those who resisted as rebels. In most cases, however, it would appear that soldiers just stormed villages—often at dawn—without any previous warning. They told people to move immediately without giving them much time to collect their belongings. People were often beaten to force them out of their compounds. Much of the property left behind was looted by both rebels and soldiers. A number of people who ventured to go back to their former homes soon after found them burnt down. Men told us that they were harassed and even shot at, and women raped. A resident of Paicho summarised that experience of unbearable stress with these words: “We were beaten by Government troops, who accused us of being rebel collaborators and told us to go to the trading centre.” . . . In Pabbo, Opit, Anaka, Cwero, and Unyama we met a good number of people who had direct experience of having had their villages shelled. We were told that big guns of the BM21 6 barrel type were used to fire at villages where people refused to move. . . . Aerial bombardments were used—we were told—in places like Kaloguro village, in Pabbo, Awach, KocGoma, Amuru, and Anaka. This first wave of forced displacement occurred at a time of the year which normally marks the beginning of the harvesting season. Given the fact that in most cases people were not given time to collect any foodstuff, their crops remained in the fields or in the granaries. In Pabbo and Opit people told us that there were cases of Army helicopters being used to collect foodstuff from abandoned villages. Force was also used by the UPDF some months after the camps were started, in order to compel back into the camps communities who had gone home to tend their fields. We heard this complaint in every camp we visited in Gulu and in some in Kitgum.7

The frequent justification offered by NRM and UPDF officials for the forced displacement of the Acholi people is that it was to protect the latter. In fact, the name officials often give the camps is “protected villages.” However, such justifications do not stand up to empirical scrutiny for the straightforward fact that the NRM/UPDF did not adequately protect the camps, even when they had the military capacity to do so.8 Instead, the camps served as LRA magnets, and most of the worst massacres occurred in the camps. People I interviewed confirmed this experience of being left vulnerable:

What experiences in Alero camp did you go through?

Yes, in Alero camp you were never safe. The rebels… attacked the camp. They burned up people’s huts. They robbed things from people. In the camp, they abducted people—both children and elders. Some of them have never come back. They went with the rebels and we have never heard about them.

When the rebels came to Alero camp, where would be the government soldiers, the military? Was the camp not protected by the military?

The government soldiers who were protecting us were few. Many times when these people [the LRA] came, they [the government soldiers] ran away. They could not protect the people in the camp, and the rebels would abduct people at will. The rebels would burn houses at will. The rebels would do whatever they wanted at will.

While the camps were left vulnerable, Salim Saleh, the President’s brother, moved to secure the freed-up land. The Acholi Religious Leaders Peace Initiative reported on this activity as well:

Soon after the forced removals of people from the countryside, Maj. Gen. Salim Saleh started some kind of commercial farming business in Kilak country, engaging people in this enterprise under conditions tantamount to exploitation, since people were given money to engage in farming but had to repay double the amount after the harvest. According to former MP of Cwa constituency Okello Okello, “people were so desperate that many engaged in this kind of business.9

Saleh controls the Sobertra Construction Company in northern Uganda, which, among other things, has built security roads that are off-limits to the civilian population. The anthropologist Sverker Finnstrom describes an encounter with one of the Sobertra vehicles, a truck with a heavy machine gun bolted in the back. A local Acholi commented to Finnstrom after the vehicle passed:

They claim that they are building roads, to destinations we don’t know…. Sometimes they behave like soldiers, they drive Pajeros [a 4×4 SUV made by Mitsubishi]. The normal people of Acholi, the indigenous people, are not allowed to reach that end where these people are working, for reasons best known to them. And this is the land that even people who have gone into exile have faith and hope in, the land that they hope will be for the future generation of Acholi [in keeping with the tradition of customary tenure].10

Where are the Sobertra Construction Company roads intended to go? Saleh’s actions provide information. The land study cited above describes a 1998 project “initiated by a senior army officer” to give loans to farmers to implement mechanized farming on 250 acres of land in Amuru district in northern Uganda. The hitch is that the actual landowner never gave consent for this project. The officer? Salim Saleh. The report goes on to describe a 1999 proposal by “a company for turning Northern Uganda into the breadbasket of central Africa.” The company’s proposal itself claims that there are “vast, highly fertile lands… available for large scale grain production.”11 The company? Divinity Union Ltd., owned by Salim Saleh. Two years later, the Acholi Religious Leaders Peace Initiative criticized the Divinity Union proposal. “During our consultations with people in the camps many expressed the fear that the policy of putting the population of Acholi in camps was a well-calculated move in order to grab their land. A project proposal two years ago by the Divinity Union Ltd., owned by Major General Salim Saleh, highlighted some large chunks of land in Acholi to be used for large-scale commercial farming.” The situation with Saleh and Divinity Union, according to the religious leaders, “deepens the already existing rift between the people of Acholi and the National Resistance Movement (NRM) Government.”12

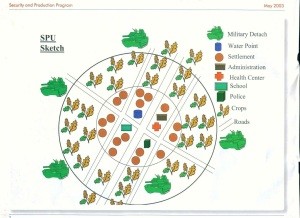

Undeterred by criticism from the Acholi religious leaders and other advocates on behalf of Acholi land rights, Saleh and Divinity Union proposed a “Security and Production Programme” (SPP) in 2003. The Production Programme’s plan is for all Acholi customary land “that is not tilled, being grazed on, or privately registered” to be turned into militarized working farms, with local youth recruited and trained by the government to protect the fields. Though the SPP literature nods towards consultation with local traditional chiefs regarding the land, it states that the Production Programme is really a “government Project Implementation Unit” to be run by the central administration offices, including the Ministry of Defense. Ostensibly proposed as a way to reduce population dependence on food aid during the war, SPP, if implemented, would place all Acholi customary land not being actively tilled under government control and have Acholi work the land not as landowners but as low-wage laborers or quasi-serfs. Acholi Ministers of Parliament and advocates have resisted the proposal, and it has not been implemented thus far. For purposes of the memo under discussion, however, this history underscores that the motives and actions on the part of both Museveni and Saleh have been entirely consistent with the stated intent of “control” of Acholi land as given in the memo. Just how militarized and controlled the farms would be is evident from pictographs from the SPP’s own literature:

In short, Museveni and Saleh unilaterally declared that it was necessary to forcibly displace the Acholi peoplef—that is, to use the military and armed attacks to move them off of their own land against their will—for the Acholi’s own “protection.” Museveni, through the UPDF, failed to provide that protection. However, Saleh still found there to be enough military wherewithal to protect the government SPP farms on land formerly held by the Acholi and upon which the Acholi were to serve as serf-like laborers. The evidence indicates that the motivation and goal of the camps was takeover of the land, not the protection of the people.

A Pattern of Scramble for Wealth: Uganda in the DRC

Shortly after his displacement mandate for northern Uganda, Museveni committed thousands of troops to the Democratic Republic of Congo, where they could be used to acquire not just land but diamonds, gold, and other gems and minerals. The DRC case is informative for two reasons. First, it establishes a thoroughly documented pattern of activity by Museveni and Saleh where they together utilize the Ugandan military for their own economic benefit in a way that directly harms, often lethally, large numbers of civilians. Second, it shows that Museveni and Saleh could have provided, had they wanted, sufficient military support at the Ugandan IDP camps to protect the Acholi civilians, but that the necessary forces were used elsewhere and for other purposes.

In 1997, Uganda helped Laurent-Desire Kabila push dictator Joseph-Desire Mobutu from power in the DRC. Afterwards, however, Kabila requested that the Ugandan forces leave the DRC. This action threatened Uganda’s interest in the DRC’s natural resources, so in 1998 Uganda, according to a recent UN report, “created and supported” a rebel military and political movement—the Mouvement pour la liberation du Congo (MLC)—and found Jean-Pierre Bemba, the son of a Congolese billionaire, to head it up.14 Between 1998 and 2002, Bemba gave the Ugandan government mining concessions in the areas he controlled in exchange for military support.

In 2002, a United Nations report specifically identified Saleh as a key player in the illegal exploitation of minerals in the Democratic Republic of Congo by the NRM.15 On top of that, Saleh was the primary shareholder of the Victoria Group, which, according to the UN report, was involved in the production of counterfeit Congolese francs. In other words, Saleh was having raw materials illegally extracted from a war-torn country and then was purchasing the materials with counterfeit money. In 2005, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) found Uganda, again with Saleh specifically named, guilty of the illegal extraction of raw materials and ordered it to pay the DRC $10 billion in restitution, an amount that remains unpaid.16

Importantly, the ICJ also found Uganda guilty of killings, torture, and other atrocities committed on civilian Congolese, though the International Criminal Court has yet to charge Saleh with war crimes or crimes against humanity. Again, his primary collaborator in the DRC was Jean-Pierre Bemba, who has since been indicted by the ICC on four counts of war crimes and two counts of crimes against humanity, but only for those crimes which he committed in the Central African Republic. If the ICC chose to indict Bemba for his crimes in the DRC itself, Saleh, given the ICJ judgment, would clearly be implicated, if not charged.17 Like with northern Uganda, Saleh in the DRC was fomenting and using a situation of insecurity and armed conflict to obtain personal and familial wealth. He is, by most accounts, one of the wealthiest people in Uganda.

What the cases in DRC add to the discussion of Uganda thus far is that they make clear, by the ICJ’s own account, that the UPDF on behalf of Museveni and Saleh is willing to commit violent and even lethal crimes against persons for the purpose of securing wealth. The most recent report—October 2010—from the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights makes this abundantly clear. The publication is a “mapping report” of the worst atrocities committed in the DRC between 1993 and 2003. Included among its findings are multiple instances where the UPDF or Congolese rebel factions operating with the support of the UPDF committed acts that fit the legal definition of war crimes and crimes against humanity. With regard to the town of Beni, for instance, the report states:

UPDF soldiers instituted a reign of terror for several years with complete impunity. They carried out summary executions of civilians, arbitrarily detained large numbers of people, and subjected them to torture and various other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatments. They also introduced a particularly cruel form of detention, putting detainees in holes dug two or three metres deep into the ground, where they were forced to live exposed to bad weather, with no sanitation and on muddy ground.18

In the Ituri district, UPDF forces backed ethnic Hema-Gegere militias and also participated directly in what the UN report calls, unflinchingly, a “campaign of ethnic cleansing” against the Lendu people.19 For instance, the reports states,

Between June and December 1999, UPDF and APC soldiers killed an unknown number of Lendu civilians in villages in the Djungu region close to concessions claimed by Hema-Gegere forces…. Numerous victims died when their village was set on fire or following heavy arms fire directed at their homes. Some victims were shot dead at point-blank range.20

The list of UPDF massacres of the Lendu people in Ituri district goes on:

- Between January and February 2001, UPDF soldiers attacked around 20 villages in the Walendu Tatsi community [in Ituri], killing around 100 people, including various Lendu citizens. During the attacks, the soldiers committed rape, looted, and caused an unknown number of people to disappear.

- On 3 February 2001, members of the Hema militias and UPDF troops killed 105 people, including numerous Lendu civilians.

- In January 2002, UPDF troops and Hema militiamen opened fire on the population of the village of Kobu… killing 35 Lendu civilians…. Those responsible for the massacre were trying to remove Lendu populations from the Kobu area, close to the Kilomoto gold mines.

- Between February and April 2002, elements of the UPDF and Hema militiamen killed several hundred Lendu civilians in the Walendu Bindi community in the Irumu region. They also tortured and raped an unknown number of people.21

The official response from the government of Uganda to the UN report chastises its authors for overlooking Uganda’s contribution to “peace and security” in the region.22 However, like with northern Uganda, peace and security turn out not to be the real reason for their presence at all. Indeed, when six members of the International Committee of the Red Cross sought to bring humanitarian aid to the Lendu people, they were attacked and killed. Local sources interviewed by the UN pointed to UPDF soldiers and Hema militiamen. Moreover, when Uganda did seek to unite the fracturing groups in the Ituri district, it did so by forcing the various groups to join under a yet another Ugandan-created, Bemba-headed politico-military movement, this time the Front de liberation du Congo (FLC). In other words, when local conflict threatened mineral exploitation, the Ugandan government’s response in the DRC was to forcibly realign the splintering groups under its own business partner, Jean-Pierre Bemba.23

This last particular effort did not endure long, but the pattern of alliance of convenience is clear. Indeed, by later 2002, Uganda switched sides to join with the very parties—the DRC government and its militias—it had been battling for years. Now the groups it was backing were massacring Hemacivilians.24 The 2010 UN report comments, “The lure of money was one of the reasons why opposing groups would suddenly join ranks or why the closest allies would unexpectedly turn against each other.” This was the case around the town of Kisangani, where the Ugandan army “obtained significant revenue from trading diamonds.” In Ituri district, the prime lure was gold, which was, “exported through Uganda, then re-exported as if it had been produced domestically—a similar model to that used for diamond exports.”25

The case of Uganda’s presence in the DRC is important because it helps to establish a documented pattern of behavior whereby economic greed and politico-military power join and issue forth in repeated atrocity. The conclusion of the 2010 UN report is unstinting. The political and economic agenda of the Ugandan government caused “massive and widespread violations of human rights and international law.” The authors of the report are clear that they constitute a fact-finding rather than a judicial body; still, they do not hesitate to place these violations under the descriptions of war crimes and crimes against humanity. The only difference between NRM/UPDF behavior in the DRC and that in northern Uganda is that in the former the greed is for precious gems and minerals and in the latter it is for arable land. The outcome for the resident civilians has been the same.

In the meantime, President Museveni has promoted his brother Saleh to full General and has recently made the latter the Minister of State for Microfinance. This, despite the fact that Saleh has been implicated several times in schemes where he uses his military position, granted by his brother Yoweri Museveni, for personal financial gain. Early allegations of corruption led to Saleh being dismissed as Army Commander, but Museveni reappointed him as Senior Presidential Advisor on Defense and Security. Saleh had to leave this latter post because of a bank scandal and an arrangement where he gained $800,000 from the sale of junk helicopters to the army. Still, he continued to be promoted in rank. Now there is the UN evidence of crimes against humanity, war crimes, and possibly genocide in the DRC.

It is clear, then, that the aim of Museveni and Saleh has not been that of security and peace in either the DRC or northern Uganda. Rather, it has been the accumulation of wealth, whether in the form of precious gems and minerals or arable land. Moreover, as documented in the UN mapping report, they have demonstrated in the case of the DRC that they are hardly averse to “reducing the population” where the presence of civilians is an obstacle to the accumulation of wealth. Together, Museveni and Saleh function as the political and economic wings of the Museveni family regime, now going on twenty-five years. The connecting link between the political and economic wings is a military designed and trained to meet the objectives precisely as Museveni and Saleh have constructed them.

Neopatrimonialism: The Link Connecting NRM Actions in Acholiland and the DRC

The above facts fall into place when we understand Museveni’s regime as a form of rule that political scientists call “neopatrimonialism.” A political order constitutes a neopatrimonial regime when political authority is personalized in the relationships between the primary leader—in this case Museveni—and his clients, often family members—in this case Salim Saleh—who people the bureaucracy. Michael Bratton describes such a regime this way: “Corruption, clientelism, and ‘Big Man’ presidentialism—all dimensions of neopatrimonial rule—tend to go together as a package.”26

Rune Hjalmar Espeland and Stina Petersen take neopatrimonial analysis and use it to assess the military in Uganda. They note that, as a practice, neopatrimonial rulers use their personal authority to bypass formal and merit-based structures of military advancement. Such rulers “often prefer their own ethnic group for prominent military positions, or else long-term political allies or family members.”27 Saleh is all three—clan member, political ally, and brother. Espeland and Petersen go on to point out that neopatrimonial rulers “often encourage corrupt, yet individually benefitting business practices within the military.”28 The aim of such an arrangement is to keep the members of the military loyal. Disloyalty results, minimally, in loss of income for the officers. This explains why, despite multiple instances of being caught in corrupt practices, Saleh continues to be promoted and given added powers. In fact, when an embezzlement scandal broke regarding illicit payments to “ghost soldiers” —one way officers pad their income is to list non-existent soldiers on their payroll—Museveni placed the corrupt Saleh on the committee to investigate the situation.29

Espeland and Petersen’s article demonstrates that the loyalty- and income-producing purpose of the military in neopatrimonial regimes results in an unprofessional military. The authors cite the neopatrimonial structure of the Musveni regime as a key reason for the inability of the NRA/UPDF to defeat the LRA. Despite the President’s repeated fervent claim to have the desire to defeat the LRA, maintaining client relationships with those in the military—relationships that allow and even encourage individual enterprise on the part of the officers at the expense of the local population as part of the agreed-upon arrangement with the officers—is more important than developing a level of military professionalism that is capable of victory in the conventional sense. For instance, strategic planning does not take into account that high numbers of the armed forces are “ghost soldiers” padding the officers’ income; when it is time to go to battle, these officers cannot say that the soldiers do not exist without implicating themselves, and so they enter engagements with far fewer personnel than planned. It is not by accident, then, that NRA/UPDF soldiers have been proficient at terrorizing the local populace but muddling in their ability to fight the LRA.

It is important to note, however, that “unprofessional” does not in all instances mean “haphazard.” In fact, as we will see further below, the NRA/UPDF have often been brutally efficient in pursuing their purpose: to repress civilian populations and exploit local resources for personal wealth and gain. The issue is not whether the NRA/UPDF have been organized or not, but rather what they have been organized for. In addition to fleeing at the sight or even rumor of LRA being in the vicinity, the NRA/UPDF, according to multiple reports, committed its own acts of violence and even atrocity.30

The results for the populace in northern Uganda have been disastrous. Espeland and Petersen state, “As a military strategy, the regime failed to defeat the LRA but politically they controlled most of the civilian population for two decades.” As we have seen, this has been the plan all along: control of the people—and land—in the North. The authors conclude that the humanitarian crisis that followed was a “direct outcome of the military approach to the region pursued by President Museveni.”31 As we will see in more detail in the next section, the Acholi people, according to Museveni, are not people at all.

Given the present lull in the NRM-LRA conflict, at least within Uganda, Museveni and Saleh can no longer use military force, at least not in the same way as before, as a means to cause and take advantage of social disruption in order to procure wealth. They must at least appear to be taking normal political channels, and this Museveni and others in the NRM have tried to do. Starting in 2007, Museveni sought to allocate 40,000 hectares of land in the North to the Madhvani Group for a sugar cane plantation, a number that he reduced to 20,000 hectares when faced with opposition.32 If such a deal goes through, the central government will have a forty percent stake in the plantation.33 Another case occurred when the central government gave one billion Ugandan schillings to twenty army officers and government officials to take land in the North that was already under customary tenure, resulting in the eviction of families from their land. A case of local officials getting in on the act occurred when the members of the Amuru District Land Board applied for 85,000 hectares of land for themselves, an application that, if successful, would have evicted—that is, again, displaced—10,000 people from their land.34 More recently, Museveni, Saleh, and Museveni’s son, Lt. Col. Muhoozi Kainerugaba, have been cited by the anti-corruption NGO Global Witness for arranging “security” for newly found oil deposits in ways that enhance themselves financially.35

Although the dynamics are still neopatrimonial in these more recent cases, accessing the natural resource of land is more difficult because there is no longer the social disruption of armed conflict to act as a screen for forced displacement and military rule in northern Uganda. Museveni must at least appear to be following the rule of law in order to continue to receive the high rate of foreign aid to which he has become accustomed. To his advantage is the fact that, for the geopolitical reasons indicated earlier, U.S. officials want and need to interpret Uganda’s politics not as neopatrimonial but as democratic and law-abiding. Until this structural situation of mutually reinforcing interests changes, the de facto burden of public proof will always be on those who interpret Ugandan government’s polity as something other than democratic, even when such interpreters have the far greater evidence in their favor. The memo I received is one more—and one more significant—piece of that evidence.

The Language of the Memo: The Acholi as “Backward,” “Chimpanzees” and “Monkeys”

So far, we have seen that the memo is consistent with both the earlier and later policies of Museveni and Saleh towards northern Uganda. As we have also seen, whenever domestic persons or organizations—whether members of the media, ministers of parliament, or NGO representatives—have spoken out about the arrangement and situation just described, Museveni has used his plenary political power to silence the critics. This is a large part of why, even given the evidence presented above, the actions of Museveni and his military, according to Espeland and Petersen, “have received much less attention by scholars than the atrocities of the LRA.”36 However, Museveni has gone well beyond merely suppressing these accounts and has gone on to provide and justify his own. It is at this point that the language of the memo is important.

The author of the memo refers to “the backward northerners.” This language of backwardness and, its analogue, primitiveness is consistent with Museveni’s own public and documented statements. Indeed, statements from the President to this effect bookend the conflict in northern Uganda. As early as 1987, in reference to the fight with the Holy Spirit Movement—the Acholi precursor to Kony’s LRA—Museveni claimed, “This is a conflict between modernity and primitivity.”37 As late as 2006, at the installation of Sabino Odoki as Auxiliary Bishop of Gulu, and just a month before the ceasefire with the LRA, Museveni declared, “We shall transform the people in the north from material and spiritual backwardness to modernity.”38 Thus from the beginning of the conflict up to the ceasefire agreement, Museveni has drawn upon the lexicon of backward/primitive versus civilized/modern to frame the situation. His making such statements at the installation of an Acholi bishop indicates that he is hardly ashamed of such language.39

It is noteworthy that his use of these terms bridges his switch from Maoist/Marxist guerilla to World Bank neo-liberal. The one constant is his affirmation of what anthropologists describe as a unilinear view of social evolution. Museveni makes clear in his autobiography that, in his words, “the laws of social evolution” drive his policies.40 The use in the memo, then, of the terms “Chimpanzees” and “Monkeys” is a consistent continuation of his frequent usage of the words “primitive” and “backward” to denote the Acholi. The link between the two is the language of evolution as a means of distinguishing peoples—again, it is a language much more basic to Museveni’s lexicon than the differences between Marxism and neo-liberalism. Primitive versus modern is simply the social evolutionary articulation of the biological evolutionary distinction of monkey versus human. In other words, chimpanzee = monkey = primitive = backward; human = civilized = modern. Sometimes Museveni describes the Acholi as primitive not-yet-humans; at other times he describes them as animals incapable of ever becoming human. The underpinning language of unilinear evolution is the same, and the violent policies and acts they are used to justify on behalf of “civilized” and “modern” humanity are little different.

Although there are many statements attributed to Museveni and the NRM that discount the Acholi as not simply “backward” or “primitive” but as less than human, these are sometimes difficult to verify. Two such statements stand out, however. In his first address to Acholi elders in a gathering at the Acholi Inn, a hotel in Gulu, in 1986, a number of the participants report him as saying in reference to the Acholi people, “We will put them in a calabash like nsenene(grasshoppers) and let them bite themselves to death. In this way we will rid Uganda of gasiya (nuisance) once and for all.” He is reported also to have made similar such statements referring to the Acholi as grasshoppers in addresses at Kaunda Grounds in Gulu in 1987 and 1988. Museveni’s head of the Army Political School in Entebbe, Kajabagu Ku-Rusoke, has been even more direct. For the record in a statement to the Uganda Human Rights Commission in August 1987, Ku-Rusoke said, “We don’t count those who oppose us as people.”41 And again, Saleh’s description of the North as “unpopulated” and thus ready for exploitation, despite the million-plus people there, elaborates in a pragmatic way the underlying viewpoint: the Acholi are not people. The context of a memo not intended to be distributed, but read only by his brother and ally, allowed the usually verbally careful Museveni to extend and state more explicitly the meaning of the “backward” versus “modern” language he uses in public speeches. The Acholi are “Chimpanzees” and “Monkeys,” and are therefore not human at all. It is legitimate, therefore, to forcibly round them up—beat or shoot them if necessary—so that land can be made available for exploitation by Saleh and others.

Naming Names: Codenames, the “Rebels,” Betty Bigombe, Chefe Ali, and Tinye

The memo names several persons or groups, and for clarification as well as verification it is important to identify them. The first and most important set of names is the codenames “Tremor 1” and “Meteor Plus One.” I have spoken with a former high-ranking NRM official who has confirmed the authenticity of those names as they apply to Yoweri Museveni and his brother, Salim Saleh. Given the use of codenames, it is interesting that the author of the memo chose to sign it “YKM.” Why would Museveni use codenames and then sign such a statement in his own initials? Here, I think it is important to remember that this memo was never intended for circulation beyond the author and the recipient and perhaps a small circle of others. In this instance, the codenames are not for the purpose of secrecy but for rhetorically signifying the nature of the communication as being official and of political and military import. A ready analogy comes from the academic setting. If an article of mine is accepted by a journal, the journal’s editor, even if she knows me quite well and addresses me by first name on other occasions, addresses the acceptance letter to “Dr. Whitmore” or “Professor Whitmore.” The editor’s name at the end of the letter will be typed with a formal title, but she may, as is often the case, simply sign her first name. It is hardly surprising, then, that Museveni would sign personally a similarly formal memo “YKM.”

The “rebels” referred to in the memo should not be mistaken for the LRA, which had yet to be formed. Described as “roaming around” rather than in attack mode, the “rebels” likely refers to the remnants of the UNLA and other splintered and defeated groups. Again, the UNLF, which gave birth to the UNLA, was a force forged from twenty-eight rebel groups. Within two years of Museveni’s victory, the number of rebel groups in Uganda was back up to twenty-seven.42

Of interest is the memo author’s description of the rebels as simply “roaming around”—not “regrouping” or “attacking.” There is no sense of military urgency on the author’s part. This is the memo of a victor. The lack of military urgency sits flush with political scientist Adam Branch’s finding that at first there was initially no insurgency against Museveni’s regime. When the NRA came north—looting, raping, and killing, as we will see—there was no opposition. Museveni, in Branch’s words, “launched a counterinsurgency without an insurgency.”43 My conversations with the people of northern Uganda who were there at the time of the NRA’s actions support Branch’s analysis. One man from Madi Opei told me the following:

When the NRA came, the people went into the cave that runs the full length of Got Latoolim< [the mountain in between Madi Opei and Agoro]. It is a big cave, so everyone who wanted could fit there. They took supplies and some of them had guns so they could stay there a long time and protect themselves.

They stayed there for two months. The NRA could not get them out. They had food, defense. So the NRA sent some Acholi who were NRA to talk them out, and after two months they came.

At first they were treated okay. But then a second detachment of NRA came and started treating them badly. Beating them. Raping. People “disappearing.” I tell you, if it were not for that bad treatment, there would not have been any rebellion. The former UNLA would have just diffused back into the community and that is it.

The UNLA that were in Sudan—they were waiting and watching to see how people were treated. If they were treated well, then the UNLA would have just gone back into the communities. When those in Sudan heard how the people in northern Uganda were treated, then they started planning [for insurgency].

In other words, the remnants of the UNLA were waiting in Sudan like the residents of Madi Opei were holed up in Got Latoolim: the primary aim was personal security until it could be determined whether it was safe to come out.

When a resistance group finally did form, it did so in response to violence initiated by the NRA. The NRA violence actually catalyzed a major transformation in the leading group from the North. The Holy Spirit Movement, which launched the first major insurgency, was initially—before NRA atrocities—a non-violent, gender-equal religious movement. Its leader, Alice “Lakwena” Auma, was a spirit medium. Only after the NRA actions did it join with remnants of the UNLA to form a fighting group. The aggression of Museveni’s “counterinsurgency without an insurgency” fits with both the aggression called for in the memo and its description of the rebels as simply “roaming around” and in disarray, thus providing further empirical evidence for the authenticity of the memo.

The memo mentions two military officers who led the NRA campaign in the North: “Chefe Ali” and David “Tinye” Tinyefuza, both of whom are known for their brutality. Their most egregious actions took place well before the formation of the International Criminal Court and so are not punishable by that body. However, the actions that took place under their command do establish a pattern of intent that becomes important in the argument concerning genocide punishable by the ICC. That argument turns on the forced displacement of the Acholi people into squalid Internally Displaced Persons camps, where thousands of them died from preventable causes. The frequent verbal defense for the formation of the camps is that they were formed for the people’s own protection, thus the government’s frequent reference to them as “protected villages.” However, given the ill treatment of the Acholi civilian population at the hands of the NRA/UPDF in the pre-camp years, the idea that the camps were then formed for their protection is absurd. The requisite ideational and psychological reversal on the part of Museveni, Saleh, and the troops from attacking people they considered to be less than human to protecting those people under dangerous circumstances as if they were their own is too fantastic to be believable.

Chefe Ali’s given name is Eriya Mwine, and he was an early ally of Museveni. He served under Museveni in FRONASA (The Front for National Salvation), a rebel group that Museveni formed in 1973 when he split off from the mainstream opposition to Idi Amin. FRONASA joined temporarily with the other rebel groups—twenty-eight groups in all—to form the Uganda National Liberation Front (UNLF). The UNLF, in turn, allied with the Tanzanian army to oust Amin in 1979. Museveni became the Minister of State for Defense in the UNLF government in Uganda. Infighting ensued almost immediately with multiple plots and counterplots, with Museveni demoted to Minister for Regional Cooperation. When the presidential election of 1980 was announced, he immediately formed an opposition party. After Milton Obote won, Museveni charged him with rigging the election, and formed the rebel National Resistance Army. Chefe Ali went with him. Ali commanded the NRA’s 11th battalion, which was key in taking the capitol, and he was later named one of “10 Brave Men Who Faced UNLA’s Fire.”44 Chefe Ali would be a natural choice, then, to carry out Museveni’s plans in the North. In fact, he is known for his brutality. After his death, protesters lynched his bodyguard in a demonstration of anger against the brigadier.

Museveni named David “Tinye” Tinyefuza the Director of Intelligence for the NRA during the 1980-1985 bush war. Although they had a brief falling out, Museveni promoted Tinyefuza to Brigadier and then Major General in 1988-89 and appointed him Minister of State for Defense. Museveni then set Tinyfuza as commander of Operation North, the first major operation against the LRA, until 1991. Though there is need for a formal investigation, there is already little dispute that the NRA committed crimes against humanity and war crimes during the operation. One of the most known of Tinyafuza’s actions is that he rounded up about 30,000 people and forced them into Pece Stadium in Gulu to screen for LRA combatants. He also arrested and tortured major political leaders including Daniel Omara Atubo, who has referred to Tinyefuza as “the butcher of the north.”45 More recently, Tinyefuza has had a hand in the repressive events discussed earlier in this article: he undertook the arrest of presidential candidate Kizza Besigye on the trumped-up charge of treason in 2005 and led the military siege of the High Court when it released Besigye and others in 2006.

Again, even though there is general consensus that Ali and Tinyefuza oversaw crimes against humanity and war crimes on the part of the NRA, there still needs to be a detailed investigation. I myself have recorded about 300 hours of oral history with the the Acholi people, and although I never asked about NRA/UPDF atrocities, these events often came up in the people’s accounts. One typical example:

I have a few things that I will never forget in my life—atrocious acts of killing that I have seen in my home, among my Acholi people. I will not forget this. I would see how people were arrested, and how people were tortured and eventually killed. I have seen so many young people arrested, for no reason, and taken away—some of them as far away as Luzira upper prison in Kampala. I have seen, also, young people arrested in my area, and put underground where a big hole had been dug by the military. And there, they suffered underground, and they [the military] would make bread and throw it to these people who were suffering in the ground, like little rats. I have also seen many of these young people who were thrown in the ground, in a pit, being killed by shooting, being killed by beating. Many people died in this way. They died from many causes—either you suffocated or you were beaten to death or you were shot and left dead in the pit.

I recall other things that the military were doing in the village where I lived—raping women, defiling children, and sleeping with men. This, I think, has caused HIV/AIDS. It spread around because of these kinds of abuses on the people…

One other thing that I will not forget that the military has done in this area is taking away all the possessions from people—the cattle—taking away from people whatever they had in their food store—the rice, maize, groundnuts—all foodstuffs, taking them away. The military would come and defecate in our pots where we had clean water, and they would expect you to drink this when you come, thirsty, back into your house.

Museveni himself even provided a public statement of his rationale for this kind of behavior on the part of the NRA/UPDF. “You see when you give them [the civil population in the North] a good beating then those who are using them will no longer use them. Since the month of January [1987], we have given them much beating especially in Lira and Kitgum Districts. And in fact the week I left [for Yugoslavia] we had given them a good blow in Gulu District. So it is going to settle down.”46 What this statement does not directly admit to, however, is that the “beating” often involved direct killing. Another testimony I gathered points to the fact that often the killings by soldiers were not carried out in a ramshackle way, but were planned, focused and deliberate. That is to say, the soldiers may have been unprofessional, but often they were quite effective in achieving the ends for which they were dispatched. Again, the lack of professionalism does not mean a lack of organization, but rather organization for purposes other than peace and security:

I will not forget the killing in Lacootoo. Eighteen young people were picked by the National Resistance Army of Yoweri Museveni, and they were supposed to have been brought to Anaka where there was a military base. The boys were asked to take hoes. And, with those hoes, they dug their own graves, on the mouth of River Okec. And there, they got killed, one-by-one, and buried in the graves they themselves dug.

The parents and relatives of these eighteen young men were looking for them around, and they could not find where they were. They were buried on the mouth on the River Okec—their hands and their legs having been broken, and their heads all beaten with heavy logs. The people in the area discovered the place where the young boys were buried when they went to get some reeds to prepare a granary at home. They had a strong smell, and they became suspicious about the smell. And they went to look at what was smelling—it was the decomposing bodies of the eighteen people who had been killed.

The leader of the village then invited the people whose young men went lost to come and see if any of those dead were the boys they were looking for. Indeed, those who found their sons dead took the body and went home to bury. But, these became a big source of fear for the people of the area.47

Such testimonies are important not only morally for the facts they report but legally as well, because they establish that the NRA/UPDF had no intent to “protect” the Acholi and that the idea that the NRA/UPDF—the same forces that shit in their pots and executed their children—had a sudden change of heart the moment they used armed force to drive the Acholi into the IDP camps does not stand any test of reason.

An interesting piece of evidence with regard to both Ali’s and Tinyefuza’s atrocities actually comes from the mouths of government officials and military officers trying to defend them. After the crowds at Ali’s funeral murdered a guard in protest of the brigadier’s brutality, Salim Saleh felt that he had to come to his defense, redescribing Ali as restrained. Interestingly, however, the President’s brother did so in such a way as to actually disclose the predominant pattern of NRA activity in the North, one fitting the aims and statements of the memo I received: “If it was not for Brigadier Chefe Ali, no UPC or Acholi would be alive“(italics added).48Similarly, according to one report, when UPDF Major Felix Kulayigye attempted to explain the atrocities of Tinyefuza in Operation North, he did not deny the latter’s actions but rather gave the defense, which Nuremberg rejected, that the general was simply following Museveni’s orders.49

There is urgent need for the United Nations to do a mapping report of northern Uganda similar to the one it conducted in the DRC. The mapping report ought to cover the period from 1986 through at least 1996, when Museveni first forcibly displaced the Acholi people, and preferably through 2004, when he made the third of his displacement mandates. The purpose of such a mapping investigation is both for its own sake and for the purpose of showing that the intent of the earlier NRM and military activities is at such odds with the later stated intent of “protecting” the Acholi in the camps—a difference so drastic as to be unbridgeable—that that later stated intent can only reasonably be understood to be false.

The author of the memo highlights the importance of using ambitious Acholi politicians against the Acholi people themselves and specifically mentions Betty Bigombe. From 1981 to 1984, Bigombe was the Corporate Secretary for the Uganda Mining Association. In 1986, after Museveni gained the Presidency, she won a seat in Parliament. Consistent with the aims and statements of the memo, in 1988, Museveni appointed her Minister of State for the Pacification of the North (italics added). In what I have been able to find thus far, Bigombe did not follow through in serving the aim, as given in the memo, “to eliminate some old politicians who are likely to give us troubles.”50 Instead, she would lead what would become the negotiations with the LRA that had the best chance of peaceful outcome in the 1990s. In 1994 she met with the LRA leader, Joseph Kony, who called for comprehensive peace talks with the government involving leaders of the Acholi people and members of the political wing of the LRA—essentially the same arrangement as later took place in the 2006-2008 Juba peace talks. Kony said that arranging for such talks would take six months (which it did in the case of the Juba talks). When Museveni heard the request, he gave a seven day ultimatum: the LRA forces were to surrender themselves and all weapons in seven days or the “talks” were off.

One need not be naïve about the LRA (as I indicate below, I think that the leaders ought to be formally charged with genocide in addition to war crimes and crimes against humanity) to recognize that Museveni sabotaged the 1994 negotiations just when they were getting serious. Bigombe did not do the things he hoped that she would do as described in the memo; but, consistent with that document, he nonetheless found a way to use her and what the memo describes as her “ambition.” She helped create the appearance of NRM willingness to negotiate; however, when her efforts seemed to go beyond mere appearances, Museveni had no more use for her or those efforts. Bigombe left politics soon thereafter, returning only in 2004 when international pressure mounted on Museveni to start talks anew.

What if the Document is not Authentic?

Even given the above evidence, it is possible that the memo is not authentic. If it is not authentic, it follows a pattern of disinformation that has plagued the conflict from the start. The Lord’s Resistance Army has abducted tens of thousands of people, and, in order to keep them from returning home, has sometimes forced them to kill relatives and friends. This makes the lie the LRA tells the abductees—that if they return home the people there will kill them in revenge—seem plausible. During some of the worst periods of the conflict, one of the most successful efforts in encouraging abductees to return home was that of Radio Mega, a station that broadcast the information that any returnees would not only be treated well, but would receive amnesty. The LRA does what it can to keep its conscripts from hearing the radio.

Carlos Rodriquez Soto, in his book Tall Grass: Stories of Suffering and Peace in Northern Uganda , writes that LRA officers control the youth “with a dark combination of instilling fears of terror and fascination.”51 “Father Carlos,” as he was known in the North, lived there from 1984 to 1987 and again from 1991 to 2008. (We met briefly in 2005.) He was directly involved in a number of the grassroots negotiations mediated by religious leaders. He is not sanguine about the leadership of the LRA. Through ceremonies, rituals, and beliefs “melted into a cauldron of syncretism that staggers the imagination,” the LRA leaders head up “more an armed cult than a rebel movement with political aims.” The attacks on their own people are, according to Father Carlos’ account of the rebels, an effort by the LRA to “purify the Acholi” so that the latter might better resist the government.52 Truth certainly is a casualty here.

The NRM and its military, the Uganda Peoples Defense Forces (UPDF), have also systemically bred disinformation, from underreporting LRA numbers to overstating their own successes.53 Rodriguez Soto—who is hardly pro-LRA, calling its leader, Joseph Kony, “satanic”54—provides a detailed account of the government’s handling of his own case. In order to mediate with the rebels, he had, on each individual occasion, to receive prior approval from the UPDF, which he did. However, in one instance in particular—it was late August 2002—the army used Rodriguez Soto’s peace-building efforts to track the LRA. The UPDF attacked the site, with Rodriguez Soto there, where the priest was to meet the rebels. The government forces beat and kicked him and his priest companions, took them to remote barracks, and refused them sustenance. They were not released until they signed documents that said that they had failed to secure official approval for the mediation. The army spokesperson issued a statement claiming that Fr. Carlos and his colleagues were found transporting three rebels and drugs.55

If the document given to me is inauthentic, then it must be interpreted in terms of the web of disinformation I have just described. In this view, Acholi with political grievances against the NRM government gave the memo to me in order to disseminate disinformation about Museveni. This is possible. However, given the reasons I state above, I think it far more likely that it is authentic. It is time, then, to assess the implications of the document.

- Introduction

- Part I: The Interpretive Context of Intrigue

- Part II: The Authenticity of the Document: Policy Shifts, Land, Language, and Names

- Part III: The Implications of the Document: Genocide

- Concluding Remarks

Photo by Trocaire. Creative Commons License 2.0.

Notes

- Caroline Lamwaka, “4,000 UPDAs in peace centres,” New Vision, April 8, 1988.

- Elijah Dickens Mushemeza, “Policing in Post-Conflict Environment: Implications for Police Reform in Uganda,” Journal of Security Sector Management6, no. 3 (November 2008): 4.

- Raymond Baguma, “Ugandans now richer, report says,” New Vision, October 26, 2010, http://www.newvision.co.ug/D/8/13/736212.

- For instance, the Acholi often supplement their diet by hunting anyerior “giant rat,” a groundhog or muskrat-sized rodent. Stewed well, it is tender and tastes very good.

- Judy Adoko and Simon Levine, Land Matters in Displacement: The Importance of Land Rights in Acholiland and What Threatens Them(Kampala: Civil Society Organizations for Peace in Northern Uganda (CSOPNU) and Land and Equity Movement in Uganda (LEMU), 2004), 5, available athttp://www.land-in-uganda.org/assets/LEMU-Land%20Matters%20in%20Displacement.pdf.

- Acholi Religious Leaders Peace Initiative, Let My People Go: The Forgotten Plight of the People in Displaced Camps in Acholi(Gulu: ARLPI, 2001), 9.

- Ibid.

- For further documentation on the unwillingness of the NRM/UPDF to protect camp residents against the LRA, see Civil Society Organizations for Peace in Northern Uganda, “Nowhere to Hide,” December 10, 2004. Refugee Law Project, “Statement on Ethnic Violence,” February 27, 2004, 25,http://www.internal-displacement.org/8025708F004CE90B/(httpDocuments)/300CBA7CC2650F55802570B7005A5725/$file/RLP+Position+Statement+on+ethnic+violence.doc.

- Acholi Religious Leaders Peace Initiative, Let My People Go, 10.

- Sverker Finnstrom, Living With Bad Surroundings: War, History, and Everyday Moments in Northern Uganda(Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2008), 175.

- Adoko and Levine, Land Matters in Displacement, 16.

- Acholi Religious Leaders Peace Initiative, Let My People Go.

- I am indebted to Sverker Finnstrom for making the 2003 brochure that had these pictographs available to me. I appreciate his selflessness in getting them to me. Apwoyo tutwal. The second of these pictographs appears in his Duke University Press book, Living With Bad Surroundings, 179.

- United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNOHCHR), “Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1993-2003: Report of the Mapping Exercise documenting the most serious violations of human rights and international humanitarian law committed within the territory of the Democratic Republic of Congo between March 1993 and June 2003,” 310, August 2010 (Released on October 1, 2010),http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/ZR/DRC_MAPPING_REPORT_FINAL_EN.pdf.

- See United Nations Expert Panel on Illegal Exploitation of Natural Resources and Other Forms of Wealth in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), “Report of the Panel of Experts on the Illegal Exploitation of Natural Resources and Other Forms of Wealth of the Democratic Republic of the Congo,”http://www.un.org/News/dh/latest/drcongo.htm. See also Gerard Prunier, “Rebel Movements and Proxy Warfare: Uganda, Sudan, and the Congo (1986-1989),” African Affairs103 (2004): 359-383.

- International Court of Justice, “Armed Activities on the Territory of the Congo (Democratic Republic of the Congo v. Uganda),” December 19 2005,http://www.icj-cij.org/docket/files/116/10521.pdf.

- Ssemujju Ibrahim Nganda, “Bemba arrest: Are Saleh, Kazini safe?” The Observer, May 29, 2008, http://www.observer.ug/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=102:ssemujju-ibrahim-nganda&catid=34:news&Itemid=59.

- United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, “Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1993-2003,” 349.

- Ibid., 366.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 405-408. See also 411.

- UNOHCHR, “Uganda’s Position on the Draft DRC Mapping Exercise Report,” September 30. 2010, available athttp://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/ZR/DRC_Report_Comments_Uganda.pdf.

- UNOHCHR, “Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1993-2003,” 408.

- On Uganda’s shift in allegiance, see ibid., 418-419; on massacres of Hema people, see 420.

- Ibid., 748 and 768.

- Michael Bratton, “Formal Versus Informal Institutions in Africa,” Journal of Democracy18, no. 3 (2007): 98. See also Michael Bratton and Nicolas van de Walle, Democratic Experiments in Africa: Regime Transitions in Comparative Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

- Rune Hjalmar Espeland and Stina Petersen, “The Ugandan Army and Its War in the North,” Forum for Development Studies37, no. 2 (2010): 196. It is worth noting that Saleh, Museveni’s brother, is not the only family member benefitting from military placement in the neopatrimonial system. Museveni’s son, Muhoozi Kainerugaba, joined the military as a private but is now the commander in charge of the development of the special forces. Kainerugaba is currently a lieutenant colonel, but given that the special forces has expanded to control large segments of the military, he is a de facto general.

I am indebted to one of the journal referees of the present article for pointing out the Espeland/Petersen article to me.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 202.

- See, especially, Chris Dolan, Social Torture: The Case of Northern Uganda, 1986-2006(New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2009); Robert Gersony, The Anguish of Northern Uganda (Kampala: U.S. Embassy and USAID, 1997); and International Crisis Group, Northern Uganda: Understanding and Solving the Conflict (Nairobi and Brussels, 2004). The National Resistance Army (NRA) was renamed the Uganda Peoples Defense Force (UPDF) in 1995.

- Espeland and Petersen, “The Ugandan Army and Its War in the North,” 210-211 and 208.

- See “Madhvani to set up second sugar factory,” New Vision, January 1, 2007.

- See “Kakira offered 20,000 hectares of land in Amuru,” The Monitor, November 13, 2008.

- For a careful account of these cases and of the issue of land in northern Uganda generally, see Ronald R. Atkinson, “Land Issues in Acholi in the Transition from War to Peace,” The Examiner: Quarterly Publication of Human Rights Focus (HURIFO)4 (2008): 3-9, 17-25. My account is directly indebted to Atkinson’s.

- Yasiin Magerwa, “First Family ‘too close’ to oil sector,” The Monitor, November 16, 2010, http://www.monitor.co.ug/News/National/-/688334/1051166/-/cl9icez/-/.

- Espeland and Petersen, “The Ugandan Army and Its War in the North,” 211.

- “Museveni directs final Lakwena offensive,” New Vision, November 6, 1987.

- Ibid.

- Ronald Kassimir writes that the Ugandan president is “not shy” in using such terms as “primitive” and “backward” to refer to the Acholi. Kassimir, “Reading Museveni: Structure, Agency and Pedagogy in Ugandan Politics,” Canadian Journal of African Studies/Revue Canadiennedes Etudes Africaines33, nos. 2/3 (1999): 654.

- Yoweni Museveni, Sowing the Mustard Seed: The Struggle for Freedom and Democracy in Uganda, (London: Macmillan, 1997), 26.

- See Timothy Kalyegira, “Understanding the NRM and its impact on Uganda,” The Monitor, March 15, 2008, available athttp://www.friendsforpeaceinafrica.org/timothy-kalyegira/473-understanding-the-nrm-and-its-impact-on-uganda.html.

- George Clement Bond and Joan Vincent, “The Moving Frontier of AIDS in Uganda: Contexts, Texts, and Concepts,” in Contested Terrains and Constructed Categories: Contemporary Africa in Focus, eds. George Clement Bond and Nigel C. Gibson (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2002), 354, cited in Finnstrom, Living With Bad Surroundings, 69.

- Adam Branch, “The Political Dilemmas of Global Justice: Anti-Civilian Violence and the Violence of Humanitarianism, the Case of Northern Uganda” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 2007), 146.

- Ssemujju Ibrahim Nganda, “WHO FOUGHT: 10 brave men who faced UNLA’s fire,” The Observer, June 17, 2009, http://www.observer.ug/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=3895%3A10-brave-men-who-faced-unlas-fire&catid=34%3Anews&Itemid=59.

- Badru D. Mulumba, “Waterloo or springboard?” The Monitor, July 2, 2003, available at http://www.mail-archive.com/ugandanet@kym.net/msg04708.html.

- New Vision, January 19, 1987.

- The place names have been changed to protect the innocent.

- “Chefe Saved UPC’s, Acholi—Saleh,” The Monitor, July 14, 1999, available at http://allafrica.com/stories/199907140107.html.

- “Gen. Tinyefuza’s Massacres in N. Uganda Exposed,” Jonzu News, Feb. 2, 2010, http://news.jonzu.com/z_tag/tinyefuzas. Given the strongly biased reporting of this site, it is important for any full investigation to track down this attribution to Kulayigye even though it is a question of fact and not of opinion.

- Though I have been told that one researcher has evidence pointing towards Bigombe actually carrying out this part of Museveni’s policy, I have not yet seen that evidence.

- Carlos Rodriguez Soto, Tall Grass: Stories of Suffering and Peace in Northern Uganda(Kampala: Fountain Publishers, 2009), 23.

- Ibid., 21-22. See also 43. For an interpretation of the LRA effort to “purify” the Acholi, see Branch, “The Political Dilemmas of Global Justice.”

- See, for instance, Ron Atkinson, “Revisiting Operation Lightning Thunder” and “Revisiting Operation Lightning Thunder, Part II,” The Indepent, June 9 and 16, 2009, http://www.independent.co.ug/index.php/column/insight/67-insight/1039-revisiting-operation-lightning-thunder.

- Rodriguez Soto, Tall Grass, 65.

- Ibid., chapt. 5, “The Trap of Tumangu.” Occurring in August 2002, this incident can be investigated by the ICC if it so chooses.